MURBAN

THE UAE OIL MOVING

THE WORLD

The word Murban will one day be a global reference point for the cost of a barrel of oil ... like Brent or West Texas Intermediate.

They are all types of crude oil. Brent produced from fields in the North Sea, WTI from the United States and Murban from onshore fields in the emirate of Abu Dhabi.

Murban crude has a significant role in the global energy landscape.

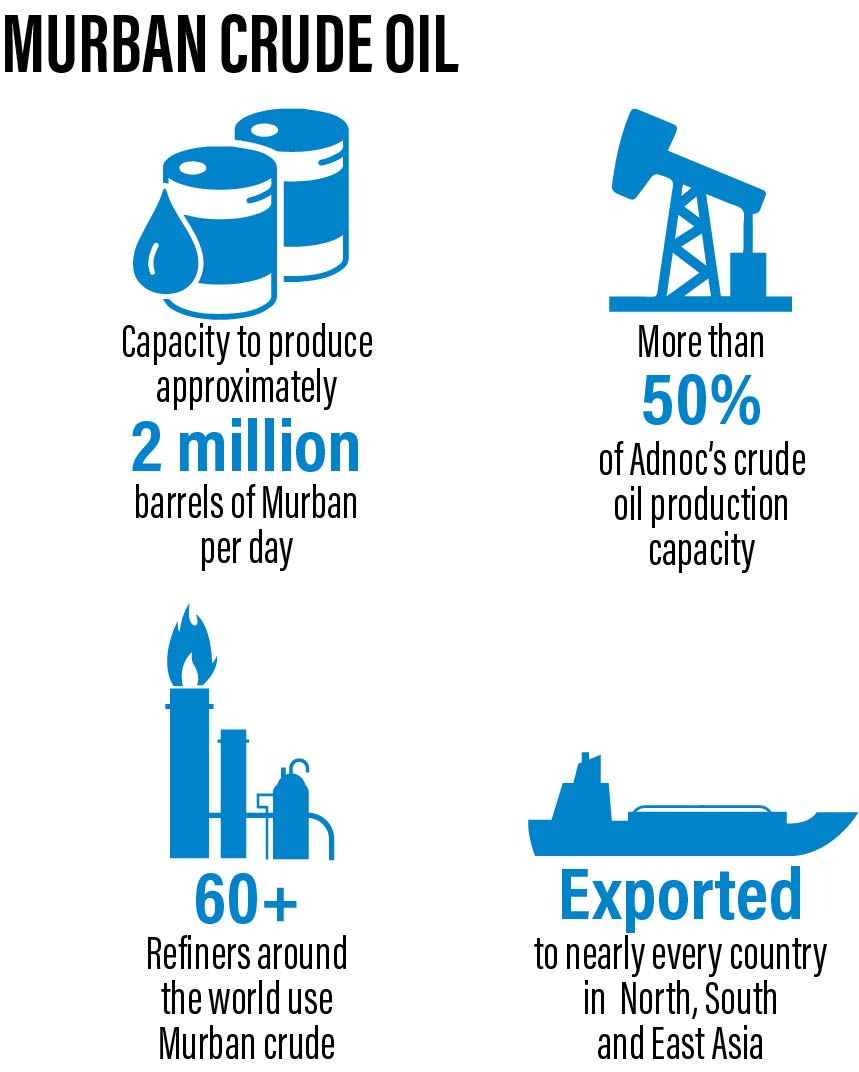

The UAE has the sixth largest oil and gas reserves in the world, most of it in Abu Dhabi. The Abu Dhabi National Oil Company has the capacity to produce about 4m barrels of crude per day, half of that is Murban.

Abu Dhabi has been pumping Murban since 1960 and it has been exported all over the world. Today, Adnoc produces Murban oil and ships it from UAE ports such as Fujairah to countries including Japan, China, South Korea, Thailand, and India.

From Monday, March 29, 2021, contracts for future delivery of Murban crude will begin trading on a commodities exchange in Abu Dhabi.

The buying and selling of Murban futures, combined with the lifting of restrictions on the resale of any oil that is bought, will turn it into a freely traded global commodity, further raising its profile.

The journey for Murban mirrors that of the UAE - both are in a new phase of prosperity and hope for the future - emerging from a vision of economic and social transformation that began decades ago.

Murban's story is told vividly below, including through the words of the workers who pioneered its fields and helped create its legacy. The current generation tasked with ensuring Murban's future also share their experiences and hopes for its continued success.

The arduous search for black gold beneath the sand

Agreements were made as early at 1939 to begin searching for oil in Abu Dhabi

Murban did not give up its riches easily.

Drilling began in January 1953, but it was another decade before the first commercial shipment of oil was exported from the new terminal at Jebel Dhanna.

Those years in between are a story of determination and dedication, of hardship, sacrifice and great cost – even to human life. They were also the first steps taken on the road to the formation of the UAE, and a prosperous future for all who live there.

The story begins even earlier, with agreements made in 1939 with the Ruler of Abu Dhabi, Sheikh Shakhbut bin Sultan Al Nahyan, that would allow foreign companies to look for oil.

The first known aerial photograph of Abu Dhabi taken in 1949. The square grounds of Qasr Al Hosn can be seen just inland. (Ronald Codrai / DCT Abu Dhabi)

The first known aerial photograph of Abu Dhabi taken in 1949. The square grounds of Qasr Al Hosn can be seen just inland. (Ronald Codrai / DCT Abu Dhabi)

Just months later, the Second World War began, with the conflict delaying the search for oil by seven years.

Finally, with peace in 1945, the first serious surveys were under way. Another four years passed before the first drilling rig began boring deep below the sand.

The first wells were dry, so attention turned to the area around what today is Habshah and Zayed City, inland from where Abu Dhabi’s first offshore oilfield would be discovered.

It was remote and desolate terrain, once thought impossible to reach except on foot or by camel, but finally opened up with the arrival of aircraft and desert vehicles like the Dodge Power Wagon, which was fitted with aircraft tyres to prevent them sinking in the sand.

Deep in the desert, a worker with his Land Rover watches a drilling rig at the Murban Bab oil field in 1964

Even so, it was a harsh environment for both men and machines. “The logistics of getting there were formidable,” says Quentin Morton, whose father worked as exploration geologist for Petroleum Development (Trucial Coast) – a consortium of oil companies holding the concession.

“Vehicles would struggle to get there. Even the Dodge Power Wagons could only get to parts of the desert,” says Morton, the author of several books on oil and the history of the region.

Men attempt to free a car bogged down in sabkha. (Adco)

Men attempt to free a car bogged down in sabkha. (Adco)

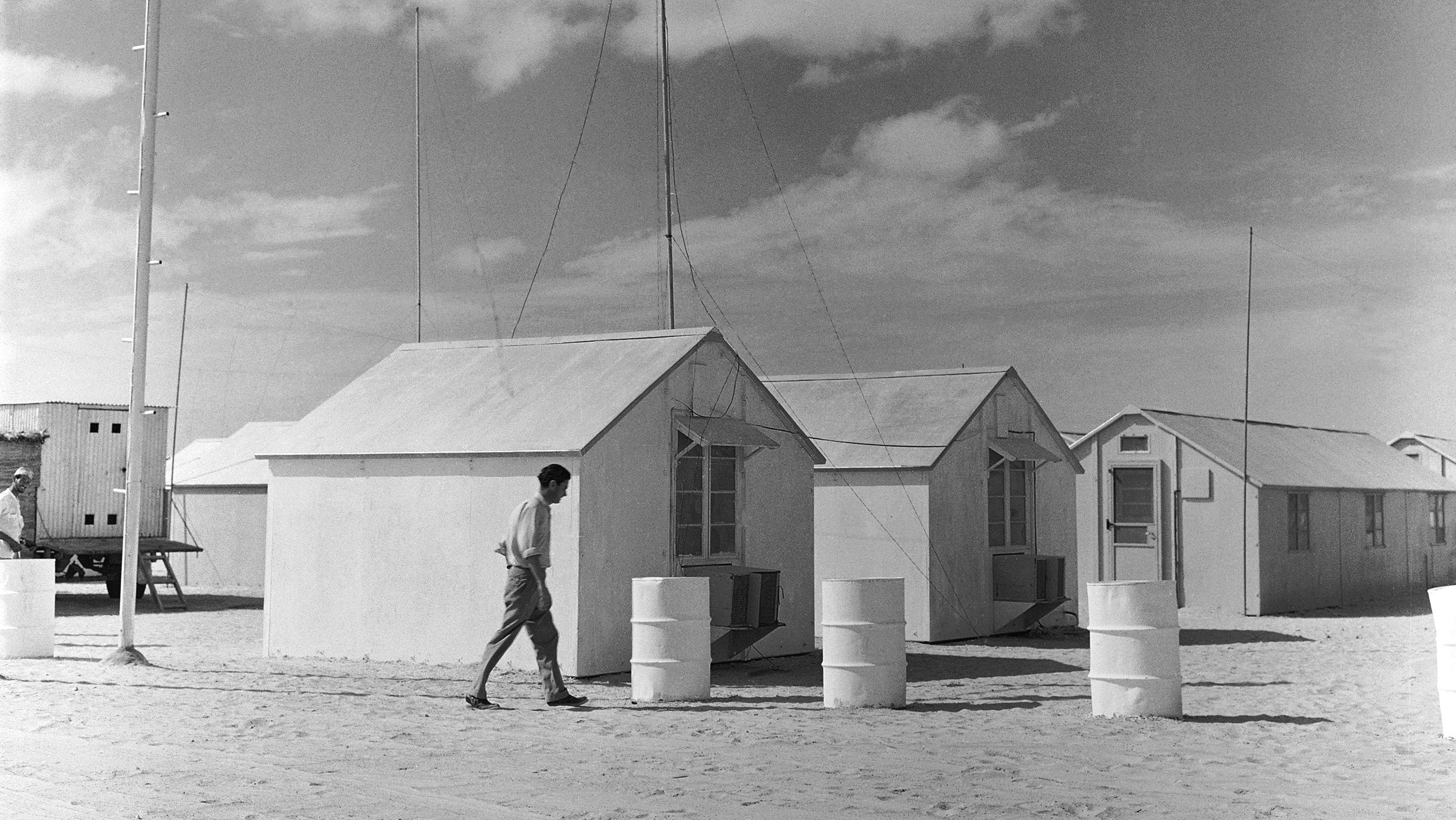

It was now early 1953. Equipment was landed on the coast at Ras Dhabayya, about 50 kilometres west of Abu Dhabi island and a base camp established at Tarif, with some of the comforts of home, including, eventually, air-conditioned caravans.

A stretch of sabkha – the saline salt flats that run along the coast – was marked out to create an airstrip firm enough to support the de Havilland Dove aircraft that were the aviation workhorses of the Gulf, and the even larger Douglas DC-3 Dakotas.

Spudding the Murban 1 well – the industry term for commencing drilling – began on January 18, 1953. The chief geologist, FE Wellings, believed that oil would be found in the 150 million-year-old rock strata known as the Jurassic Arab Zone, where Saudi Arabia had already found large reserves.

This meant digging deep and, by July, in difficult and dangerous conditions, the test well had already reached nearly 4,000 metres, without apparent success.

A month later, disaster struck. The well began to give off large quantities of highly poisonous and explosive hydrogen sulphide gas, which escaped after a pipe ruptured. Descending into the well head to turn off the main valve, engineer Gavin Johnston was overcome, along with a second man, who came to his aid. Rescuers arrived in breathing equipment to pull them free, but it was too late. Both men were dead.

Workers at the Murban 2 well in 1958. Two years, later the Murban 3 well would find commercial quantities of crude oil

The tragedy spelt the end for Murban 1. Some traces of oil had been found in rocks recovered from the bore hole but the well was in such poor condition that it was impossible to tell at what depth it had been found. Its true significance was not understood at the time.

Attention switched instead to other part of the emirate, but without success. Wells were drilled at Gezira and Shuweihat but, even at depths of 4,000 metres, still produced nothing.

Men at work at the Shuweihat 1 rig in 1965

A serious difference of opinion now emerged among the geologists working for PD (TC).

Some, headed by Wellings, wanted to continue looking elsewhere. Others suggested a return to Murban, arguing it was worth a second look. Matters were settled when the next well, far to the north in Sharjah, also came up dry but, more importantly, with the first discovery of oil in Abu Dhabi – this time under the sea.

Oil was detected in commercial quantities in early 1958 by Abu Dhabi’s offshore concession. One glance at the map showed the new Umm Shaif oilfield was barely 80 kilometres from Murban and shared the same geological features. Could this also include oil?

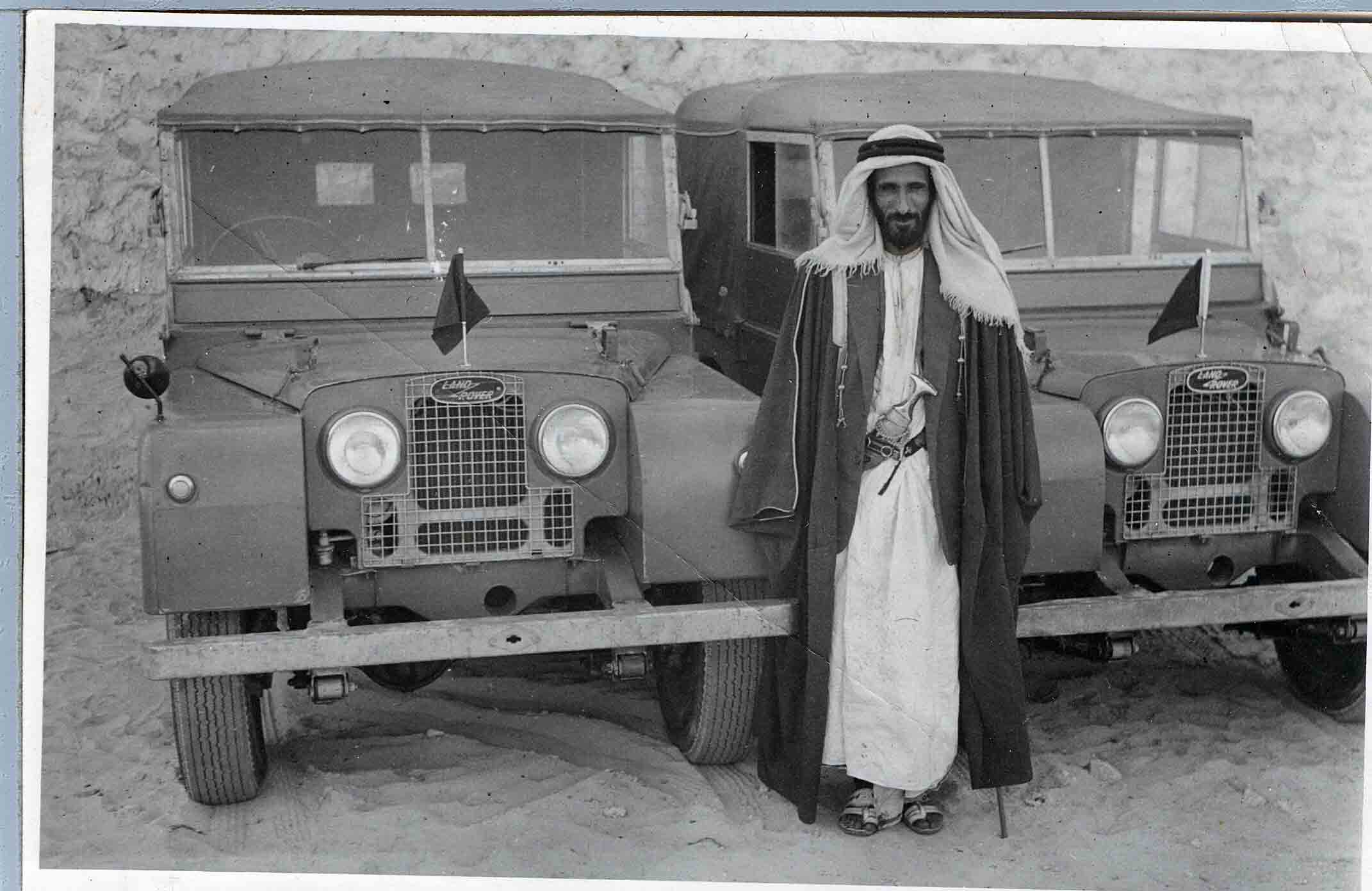

Drilling of Murban 2 began in October 1958, with a grand ceremony that included an inspection of the Tarif camp and wellhead by Sheikh Shakhbut, who arrived in his yellow Cadillac and a convoy of Land Rovers.

Sheikh Shakhbut, Ruler of Abu Dhabi, with two of his Land Rovers seen here at Qasr Al Hosn in 1956. The cars are flying the original flag of Abu Dhabi, which added a white corner in 1958. (Estate of Roderick Owen)

Sheikh Shakhbut, Ruler of Abu Dhabi, with two of his Land Rovers seen here at Qasr Al Hosn in 1956. The cars are flying the original flag of Abu Dhabi, which added a white corner in 1958. (Estate of Roderick Owen)

Again though, initially there was disappointment. After reaching a depth of 3,000 meters, there was still no sign of commercial quantities of oil.

These [oil] discoveries will completely revolutionise life in Abu Dhabi

It was third time lucky. Murban 3 was started the following year and struck a significant oilfield in May 1960. It was soon confirmed to be at least 8,000 barrels a day. With Umm Shaif and second onshore field shortly discovered at Bu Hasa, it was clear Abu Dhabi would now be a major player in the global crude oil market.

Within two years, the emirate was ready to begin production, with the wells now linked by pipeline to a deep water port at Jebel Dhanna, and the creation of the Abu Dhabi Petroleum Company.

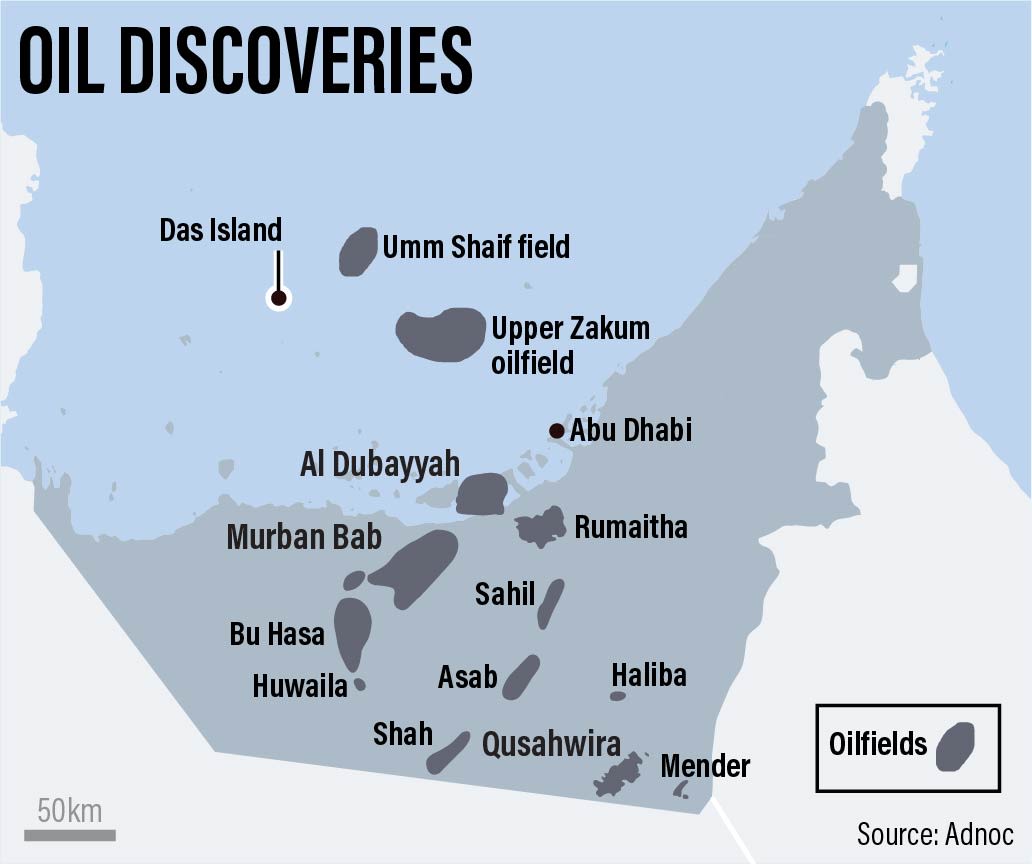

Some of Adnoc's onshore and offshore oil fields. The onshore fields are where Murban crude is extracted

Some of Adnoc's onshore and offshore oil fields. The onshore fields are where Murban crude is extracted

The news made international headlines. “New power emerges in the Middle East” wrote The Times of London in October 1962. “These discoveries will completely revolutionise life in Abu Dhabi,” the correspondent noted. For readers of the mass circulation Daily Express it was “Sheikh gets news of a gusher.”

On December 16, 1963, Abu Dhabi Petroleum Company sent a report to London under the heading Oil Exports from Murban Field.

“The first export of crude oil from the Abu Dhabi Petroleum Company’s field at Murban was shipped yesterday, December 15, in the 36,000 ton tanker Esso Dublin,” it began.

The Esso Dublin carried the first Murban crude oil shipment from Abu Dhabi to the US in 1963

The oil was destined for the Esso refinery at Fawley, on the English south coast, after, the report said “several years of extensive exploration,” and noting, with great foresight, that “the field continues to be actively developed”.

Agreements were made as early at 1939 to begin searching for oil in Abu Dhabi

Agreements were made as early at 1939 to begin searching for oil in Abu Dhabi

Deep in the desert, a worker with his Land Rover watches a drilling rig at the Murban Bab oil field in 1964

Deep in the desert, a worker with his Land Rover watches a drilling rig at the Murban Bab oil field in 1964

Men at work at the Shuweihat 1 rig in 1965

Men at work at the Shuweihat 1 rig in 1965

Workers at the Murban 2 well in 1958. Two years, later the Murban 3 well would find commercial quantities of crude oil

Workers at the Murban 2 well in 1958. Two years, later the Murban 3 well would find commercial quantities of crude oil

Workers at the Murban 38 rig in 1964, four years after striking significant oil at the Murban 2 site

Workers at the Murban 38 rig in 1964, four years after striking significant oil at the Murban 2 site

The Esso Dublin carried the first Murban crude oil shipment from Abu Dhabi to the US in 1963

The Esso Dublin carried the first Murban crude oil shipment from Abu Dhabi to the US in 1963

The Murban pioneers

THE OPPORTUNITY OF A LIFETIME

Saleh Al Wahedi worked at Adnoc for 44 years, beginning at age 17 in 1973

From brushes with death in the depths of the country's most prolific rigs to bringing bellbottoms to the UAE, Saleh Al Wahedi was among the first to trailblaze a path to become a mechanical engineer at, what is today, one of the world's biggest oil companies.

The 65-year-old Emirati, now retired, began his decades-long career at Abu Dhabi National Oil Company at age 17, having not yet completed school.

For the young man, in a young country, it was a rare opportunity but he saw in the oil industry a nascency and drive that he had in himself.

Immediately after joining, in September 1973, he began a two-year training programme with other young Emiratis to learn everything from maths and English to safety procedures. They would spend their summers undergoing work experience at different oil fields across the emirate.

“They paid us Dh200 which was considered a fortune,” he says with a chuckle.

Three workers prepare the drilling bit for an exploration well at Shuweihat on the Abu Dhabi coast in 1956. Despite reaching a depth of over 4,000 metres, the well proved dry, prompting a return to the Murban Bab field, where commercial quantities of oil were discovered four years later

Three workers prepare the drilling bit for an exploration well at Shuweihat on the Abu Dhabi coast in 1956. Despite reaching a depth of over 4,000 metres, the well proved dry, prompting a return to the Murban Bab field, where commercial quantities of oil were discovered four years later

“It was hot, there were no phones, no internet or WiFi and we had to work in the fields to get hands-on experience. It was remarkable - the best experience ever.”

Al Wahedi trained as a maintenance technician, spending the hot summer months working at the bottom of an oil rig for 12 hours a day.

Determination and luck, he says, carried him through the arduous and sometimes life-threatening experience.

“[One time,] I was on the rig floor when the shale rotated and hit my head. I was lucky that I was wearing a helmet,” he says laughing.

In those days, trips to the oil fields required a short plane ride and a 40-minute drive across the desert from Abu Dhabi city.

Workers would pack their belongings for the three months they would spend on site.

“One time, I had bought a new suitcase and put my clothes in it. We were in a Land Rover and I put my bag in the back of the car. The driver was speeding and ... I remember looking back at my suitcase and seeing all my clothes flying out of it and strewn all over the desert,” he says.

Worker accommodation at the Murban V site in 1961

Worker accommodation at the Murban V site in 1961

In late 1975, he was sent to the UK to further his training, studying at Merton College in Oxford, a polytechnic in South Wales and spending time in London.

He returned to the Emirates with a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and a new wardrobe yet unfamiliar in the UAE.

Sporting shoulder-length hair, tight bellbottom trousers and platform shoes, Al Wahedi landed in Abu Dhabi in the early 1980s looking like a long-lost Bee Gees brother.

“My brother drove me straight from the airport to the barber who asked me why I had a mop on my head,” he says.

“My family asked me to burn all my photos of my days in the UK because of what I was wearing and how I looked. Those were the best days."

Al Wahedi was part of the second small batch of Adnoc employees to be sent to the UK for training.

“My best friend, Murshid Al Romaithi, was [in the batch] before me and ... helped me when I arrived.”

Together they navigated the challenges of studying and living in a foreign country for the first time, sometimes finding themselves in embarrassing situations.

“One day I decided to venture out and see 'the pictures' everyone was talking about so I went to a place where I saw a lot of people buying tickets and asked the attendant to give me a ticket to watch a film. The attendant looked at me confused and said there were no movies here, 'this is an underground station'," says Al Wahedi.

“These are the things you can never forget. Even the food we didn’t know. For us, anything that started with the letter 'b' was beef, even bacon. This we discovered late,” he says with a laugh.

On return to the UAE, Al Wahedi gradually worked his way up through the ranks, going on to manage all Adnoc's onshore projects. It was job he relished as it allowed him to frequently visit the oil fields where he made his start.

“I started actually working at Murban in 1982. This was the best experience in my life and I was lucky to be working at such an environment with a wealth of international experience."

Murban crude is one of the biggest oilfields in the world. It is the heart of Adnoc

He says seeing Adnoc go from operating out of caravans to the point where its oil is traded on international markets alongside global brands is a national dream that has become a reality and he is proud to have played a part.

"The transformation you see today at the Murban oil field is unbelievable. I never thought we would move this fast. No one could have even dreamed it. Our target was to produce oil safely but now you are talking about tremendous capacities. Murban crude is one of the biggest oilfields in the world. It is the heart of Adnoc.”

Today, four years after retirement Al Wahedi, now a father of seven, still finds himself accidentally driving to work instead of where he was originally headed.

“It was an experience and when you remember those years later, you feel a warmth inside you."

Saleh Al Wahedi worked at Adnoc for 44 years, beginning at age 17 in 1973

Saleh Al Wahedi worked at Adnoc for 44 years, beginning at age 17 in 1973

The 'King of Shah', Hasan Al Suwaidi, at his home in Abu Dhabi

The 'King of Shah', Hasan Al Suwaidi, at his home in Abu Dhabi

THE KING OF SHAH

The 'King of Shah', Hasan Al Suwaidi, at his home in Abu Dhabi

Nestled between the dunes on the southern edge of the Abu Dhabi border is one man's heaven.

Hasan Al Suwaidi, 67, spent most of his life at Shah, working first as a plant engineer and eventually as a training manager across Adnoc's oil fields.

But it was the decades he spent transforming Shah and its surrounding area that earned him the moniker the "King of Shah".

"I set up Shah like a resort. I took birds to Shah. I bought so many things. We made Shah like heaven," says Al Suwaidi.

As operations in that part of the desert grew, as did development and infrastructure for the people who worked there.

“It is nothing like you would ever imagine. We planted trees all over ... there is a clinic a golf course and cricket."

One of the roads in the residence area was so transformed that employees would call it the Champs Elysee.

The area also became the unlikely setting for a visit from Britain's Prince Charles in 1993 as part of a private trip to the edge of the Empty Quarter.

“The biggest challenge we faced was when Prince Charles came. It required us to build a runway for a Tri-Star presidential plane for him to land in Shah. It was a big challenge but we did it,” says Al Suwaidi, who served the UK royal with a cup of camel milk.

He recalls Prince Charles telling him how amazed he was with the facilities and the cleanliness of the desert.

“We made him an Arabic tent and, when he travelled with us in the desert, ... he was surprised and said 'you travel on the sand dunes like you travel on the tarmac road'.”

Shah oil field was discovered in 1966.

A boy in Shah, one of the villages that form the Liwa Oasis. Believed to have been taken between 1950 and 1960. Shah was the ancestral heartland of the Bani Yas tribe and Al Nahyan family (BP Archives)

A boy in Shah, one of the villages that form the Liwa Oasis. Believed to have been taken between 1950 and 1960. Shah was the ancestral heartland of the Bani Yas tribe and Al Nahyan family (BP Archives)

But Al Suwaidi did not get there until the 1980s. He guesses he began his career at around 15 years old but he may have been a little older when he started training with Adma (part of Adnoc's offshore operations today).

“We didn’t have passports at the time so I decided that I would put March 1, 1954 as my birthdate. There was no reason why, I simply liked that number,” he says.

Immediately after the UAE was formed in 1971, Al Suwaidi and his friends travelled to Abu Dhabi from Zabeel in Dubai, to meet and congratulate the country's new leader, Sheikh Zayed.

“We arrived to Abu Dhabi, the new capital of the UAE and, in the morning, we went to see Sheikh Zayed. When everybody left the majlis only three of us remained. Sheikh Zayed called us over and asked 'my sons what do you need?' He said that he would like us to go to study and learn about oil. He asked us to return the next day at 6am and said he would send us to the training centre. That is how I started,” he says.

Al Suwaidi spent five years at a training centre in Abu Dhabi before being sent to the UK, where he earned a master's degree.

On return to the Emirates, he was deployed to Asab oil field in 1982.

In 1984, he travelled to the UK to pursue higher education.

“My first task was as a field service supervisor in Asab, then I joined water injection then I went to Bu Hassa for the pilot plant of gas injection."

Murban is what we call the best of the best ... It was a crescent but, putting it in the market, it has become a full moon

But Shah was where he felt most at home, tending to the field like it was his own child.

“If there was a problem with any of the oil wells, then I would be awake all night. I couldn’t sleep unless the well was producing. These oil wells are like my children, if one of the is unwell, it like my children are not well,” says the father of 14.

"I loved the oil in Shah because it was the most difficult oil to produce.

"People enjoy music but the music we most enjoyed was the sound of the oil wells producing.

"Murban is what we call the best of the best ... It was a crescent but, putting it in the market, it has become a full moon."

He says oil runs in his veins and the wells are “his heart”.

In 2015, Al Suwaidi became training and learning manager for all onshore fields.

“The biggest [achievement] of all was training all the employees who are now in management positions and are running the company.

"I trained all the labourers I could. There was no difference between the labourer and engineer on the fields because, in the end, we were looking out for the safety of all – our assets and ourselves.

"All the regulations and standards you see today were set by us,” he says.

Even the weekly desert clean ups that have been carried out all over the desert for the past 25 years were put in place by his team.

Al Suwaidi remained learning manager of training until his retirement in 2017.

"I am very proud of everything what we accomplished," he says.

"What our people did is very nice. It is unbelievable. Things that took people thousand of years, we did it in 50 years. We did it in 50 years because of our rulers - because our rulers loved us as much as we loved them."

THE INTRIGUE OF THE OIL UNDERGROUND

Mohammed Jumaa, 64, grew up curious about oil after hearing elder Bedouins speak of rigs built by the British

Mohammed Jumaa was curious about oil even before he knew what it was.

Our parents would see and talk about the exploration and drilling activities in the area

As a boy, he would hear his grandparents speak of foreign men building giant structures that bore deep into the desert sand in search for a substance that would change everything.

For the Bedouin families, the rigs were a source of intrigue. “Our parents would see and talk about the exploration and drilling activities in the area – at a time when the oil and gas were not yet reflected in the economy," he says.

"Meanwhile, nearby countries such as Saudi Arabia and Bahrain had already begun to profit from oil and gas, which was funding major developments".

The 64-year-old says they would hear of success and growth in other countries and their interest in oil only grew, yet unknowing that a wealth of black gold lay thousands of metres beneath their feet.

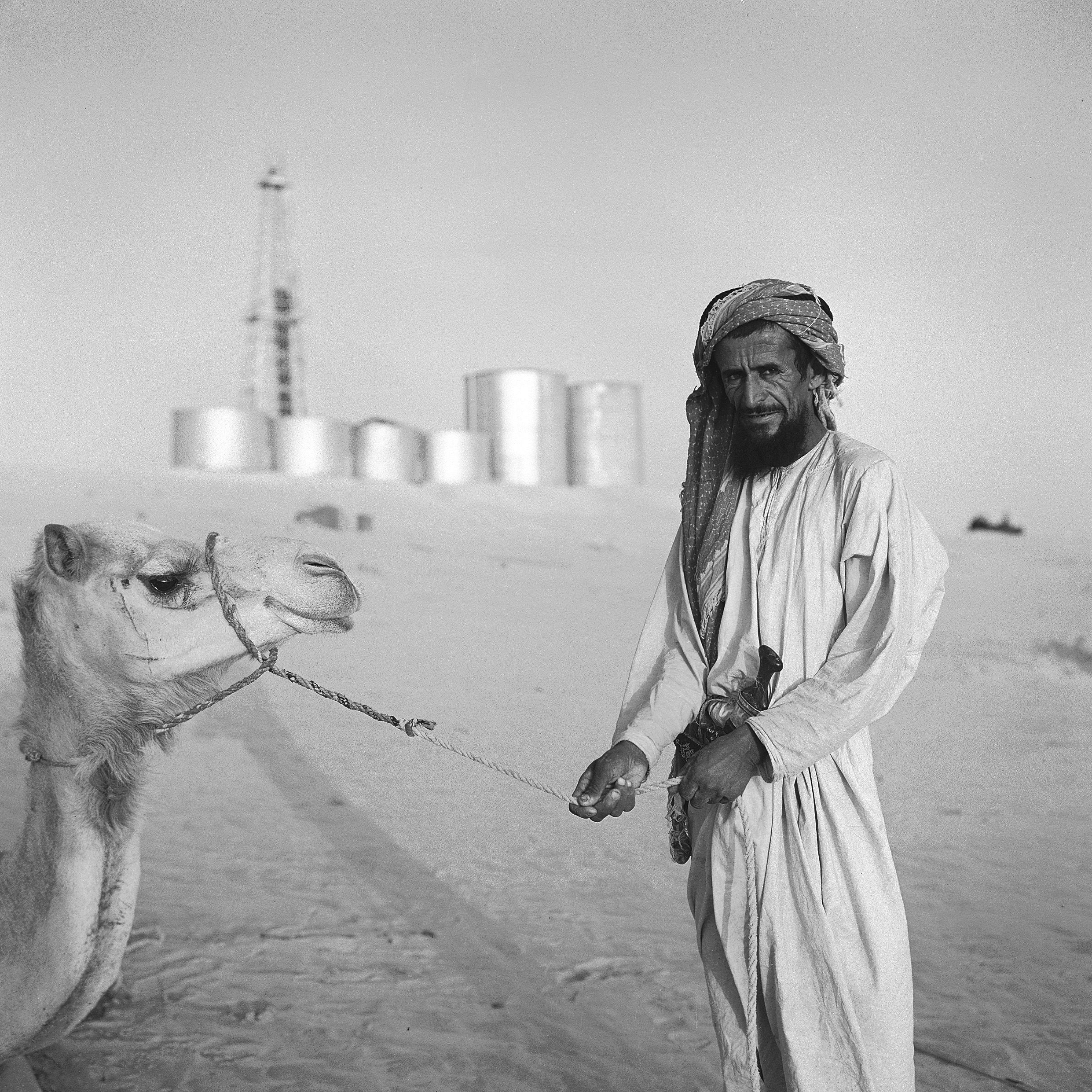

Old and new. A bedouin with his camel next to the Murban 3 oil well and storage tanks in 1960, the year commercial quantities of oil was found onshore in Abu Dhabi

Old and new. A bedouin with his camel next to the Murban 3 oil well and storage tanks in 1960, the year commercial quantities of oil was found onshore in Abu Dhabi

Early exploration activities were lengthy and fragmented with geologists struggling to strike oil.

“Fortunately, the oil discoveries in neighbouring countries such as Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Kuwait came from reservoir formations similar to those in the UAE. This motivated them to continue oil exploration and drilling activities," he says.

Eventually, giant reservoirs, such as Bab field, were found.

"The companies were able to firm up commercially viable sites and make development and production plans that were implemented to start generating oil wealth".

When Adnoc was founded in 1971, Jumaa's parents pushed him to get involved.

Abu Dhabi Petroleum Company headquarters in the UAE capital in 1971

Abu Dhabi Petroleum Company headquarters in the UAE capital in 1971

"Our parents with limited education yet great wisdom knew that ambition and hope alone in the absence of education and experience would not be good enough to meet the technical working challenges of the oil industry".

It was that encouragement and lingering curiosity from this youth that led him to join Adnoc at about the age of 18 and play a part in the growth of the company and country.

Jumaa underwent training and then, in 1976, earned a scholarship to study petroleum engineering at the University of Tulsa in the US.

He graduated five years later and returned to the Emirates to work as a drilling engineer at various onshore drilling sites.

“Working at a drilling site was amazing because it was tangible and that’s when I realised what our ancestors were talking about,” he says.

During his career at Adnoc, Jumaa was sent to the UK for brief stints with BP and ExxonMobil in the US to learn best practices and apply them in the Emirates.

Seeing the industry grow so much in a few decades and the resulting development of the UAE makes Jumaa proud.

He recalls how practices have changed over the years with innovation driving further success, such as the use of natural gas instead of burning, or 'flaring' it.

Flares on Das Island light up the night sky in 1962. Natural gas from oil production was once disposed of this way but is now recovered and sold. (Guy Gravett)

Flares on Das Island light up the night sky in 1962. Natural gas from oil production was once disposed of this way but is now recovered and sold. (Guy Gravett)

“In the early stages, you would come over the fields on planes and see flares from the associated produced gas [on rigs] being burnt, due unavailability of gas processing plants.

"Flaring the gas was a bad practice because it wasted energy and polluted the environment.

"At that time [UAE Founding Father] Sheikh Zayed issued a directive to form gas companies to process all produced gas for domestic use and export.

"Adnoc was at the forefront of this decision which turned out to be critical as the value of gas is no less than oil."

He says the discovery of Murban grade crude oil, which makes up the majority of the UAE's onshore oil output, was another game-changer.

"Adnoc has taken a very positive and strategic step by labelling and publicising Murban oil internationally, which will gain higher marketing value and demand than the rest of the oil".

Jumaa worked for Adnoc for more than four decades, becoming a senior vice president of the company until his retirement last year.

He says he "enjoyed every second" of working there, adding that Adnoc provided hundreds of young Emiratis such as him an opportunity at a time when there were few.

“Everybody working for Adnoc is part of this progress and I am sure that this progress will continue with greater success and achievements."

Mohammed Jumaa, 64, grew up curious about oil after hearing elder Bedouins speak of rigs built by the British

Mohammed Jumaa, 64, grew up curious about oil after hearing elder Bedouins speak of rigs built by the British

Carrying Murban into the future

Hamad Alraeesi is station manager of Fujairah Port but spent years on vessels, he describes as 'mini floating cities', transporting oil

Hamad Alraeesi is station manager of Fujairah Port but spent years on vessels, he describes as 'mini floating cities', transporting oil

Tahani Al Hammadi is Team Leader for Well Integrity

Tahani Al Hammadi is Team Leader for Well Integrity

A PASSING OF THE BATON

Hamad Alraeesi is station manager of Fujairah Port but spent years on vessels, he describes as 'mini floating cities', transporting oil

Hamad Alraeesi vividly recalls his visits to Dibba Fujairah Port when he was six to watch his father’s large wooden boat being loaded with electronics for export to India.

Back then, the family home was nestled in the Hajjar Mountains and was just a stone’s throw from the beach. The ocean was his second home.

Capt Alraeesi, now 35, says he always dreamed of boarding his father’s boat and making the days-long trip to South Asia. However, it never came to pass because his father was forced to close his import and export business in the early 90s.

“The ocean still played a huge part in my life. It was no longer my father’s source of income but I knew I wanted to work at sea," Capt Alraeesi, now a father of two, says.

"During my last few days studying in high school, my brothers and father used to call me Captain Hamad and they always used to say: 'Be unique, Hamad. Be unique.'

“That is when the seed was planted.”

Today, his epaulettes have four stripes to signify his rank on the ship’s bridge; the nickname of Captain Hamad as a teen became a reality in adulthood.

Capt Alraeesi’s journey with Adnoc Logistics and Services started in 2003 with a scholarship to the UK.

Aged 18, he embarked on a four-year cadet course studying nautical science. Twelve months were spent on a 250-metre vessel at sea in the north of England.

“I graduated in 2008 and have been with Adnoc ever since,” Capt Alraeesi says.

“Throughout my time here I’ve travelled to places like Japan, Singapore and Malaysia, exporting hydrocarbon products to customers around the world.

“To say your job is your passion is cliché, but for me it truly is.

As Sheikh Mohamed [bin Zayed] once said, Adnoc is in the DNA of every Emirati. Imagine a UAE without Adnoc, it would not thrive the way it has.

“From the old generation of workers that started digging in the oilfields in the 50s and 60s, to the new generation, like me, driving the industry forward, my company is the history and future of the UAE.”

Throughout his career, Capt Alraeesi climbed the ranks from third officer on the ship’s bridge, to second officer and captain.

Though he officially stopped sailing in 2015 because of family commitments, he was handed his captain’s ticket two years later and is now the station manager at Fujairah port, where he oversees all offshore operations.

“I am part of the team in charge of ensuring the safe loading of Murban oil on to our crude carriers positioned three or four miles out at sea,” he says.

“We carry out this operation through sea buoys which are connected to the underground pipeline that supplies crude from the fields in Abu Dhabi to Fujairah.

“The way I describe it to people who are unfamiliar with the industry is that we are a sophisticated petrol pump at sea, except that we require a whole team to do the job and we pump up to 2.2 million barrels of Murban on to the tanker in just 48 hours.”

In terms of tanker size, Capt Alraeesi says the vessels he tends to work on most are like “mini floating cities” and can be 300 metres long and 65 metres wide.

From the open ocean to the sandy desert, the oil and gas industry in the UAE spans the length and breadth of the Emirates.

A NEW GENERATION

Mohamed bin Amro, 56, works onshore at Abu Dhabi's Murban Bab oilfield, which was discovered in 1953.

Although bin Amro, a father of three, has been with Adnoc for 21 years, he is considered to be part of the new generation driving the industry forward.

“I finished high school and joined the Adnoc Technical Institution in 2001,” he says.

“My cousin, who is a lot older than me, used to work in the oilfields and I always used to remember being fascinated by the stories he would tell.

“As I child I was curious to know how, beneath the depths of the dry desert, there were wells filled with oil. I guess that’s when my journey into this career started.

I feel like Adnoc is the engine behind the UAE and to be a part of the team powering it is an honour.

When he graduated in 2004, bin Amro chose to work at the Murban Bab oil field.

Having grown up in the desert, he says he feels at home there.

"The ocean, water – it was never really my thing. So I chose to go to the Bab field because it was such a historic site. I took my first step on site in 2005 and started out as an operator,” he says.

“I’ve since completed a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering and I’m now the mechanical section leader on the very site where Murban was first discovered.

"Today, we extract up to 420,000 barrels a day from about 500 wells and people joke with me: they say we own one of the biggest assets in the UAE.

"These oil wells, they are like our babies.”

Working alongside Mr bin Amro is Tahani Al Hammadi, 29.

When she joined Adnoc in 2014, she was the only member of her family working in the oil and gas sector.

Today, her work has inspired three of her seven brothers to join the same company.

“I love my job and I love the significance it carries,” she says.

“The UAE has a rich history when it comes to Murban crude, but embedded within that history lies a great future, too.

“I often hear my older family members talk about how Adnoc is a major contributor to the UAE economy, so to be part of that team is an honour.”

Tahani Al Hammadi is Team Leader for Well Integrity

Having grown up in the Al Dhafra, Western Region, Ms Al Hammadi says she would travel from place to place and see road signs for the oilfields and huge platforms for drilling, which always piqued her interest.

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in petroleum geoscience, she started as a production engineer at the Bab field.

Now, just five years later, she is the “first female team leader for well integrity”.

Although production drives oil drilling, well maintenance ensures continued operations. Without it, a breakdown could hinder production volumes.

“I am tasked with ensuring that the wells run smoothly and if they are compromised in any way, it is my team’s job to maintain and fix them,” she says.

“If daily or weekly production is reduced, we have to go through the history of the well and try to decipher what the issue could be.

“For example, the water projection which helps push the oil up from the depths of the well, might not be operating to full capacity.

“We then go in and fix the water injector. There could also be scale build up so we descale the well.”

Working in shift patterns, Ms Al Hammadi works one month on and one month off, living on site during her duty period.

CREDITS

Words: James Langton, Shireena Al Nowais, Kelly Clarke, Mustafa Alrawi

Photographs (unless otherwise credited): Adnoc Group, Victor Besa / The National, Leslie Pableo, Khushnum Bhandari

Video: Nilanjana Gupta, Erica Elkhershi

Graphics and design: Roy Cooper, Nick Donaldson, Steven Castelluccia

Editors: Juman Jarallah, Mustafa Alrawi, Ian Oxborrow

Copyright The National, Abu Dhabi, 2021