Emirati women have many heroes to look up to. Dr Amal Al Qubaisi, Speaker of the Federal National Council and the first woman in the Arab World to preside over a consultative body, is one.

Others include Shamma Al Mazrui, Minister of State for Youth Affairs and the world’s youngest government minister; and Dr Noura Al Kaabi, Minister of State for FNC Affairs and chairwoman of the Media Zone Authority and twofour54 … the list goes on.

In this special report we go further back in history to the trailblazers, the ceiling breakers, the forgotten women who were the first to travel abroad for education.

Some of these women faced pressure from their parents and stigma for travelling abroad to pursue higher education at a time when it was considered taboo for a woman to travel without a male guardian.

These are the women who made it possible for Emirati women today to be anything they want to be: ministers, pilots, engineers, scientists.

In the mid 1960s, two Emiratis from Sharjah travelled to Egypt to study at a university – Sheikha Aisha bint Saqr Al Qasimi and Dr Aisha Al Sayar.

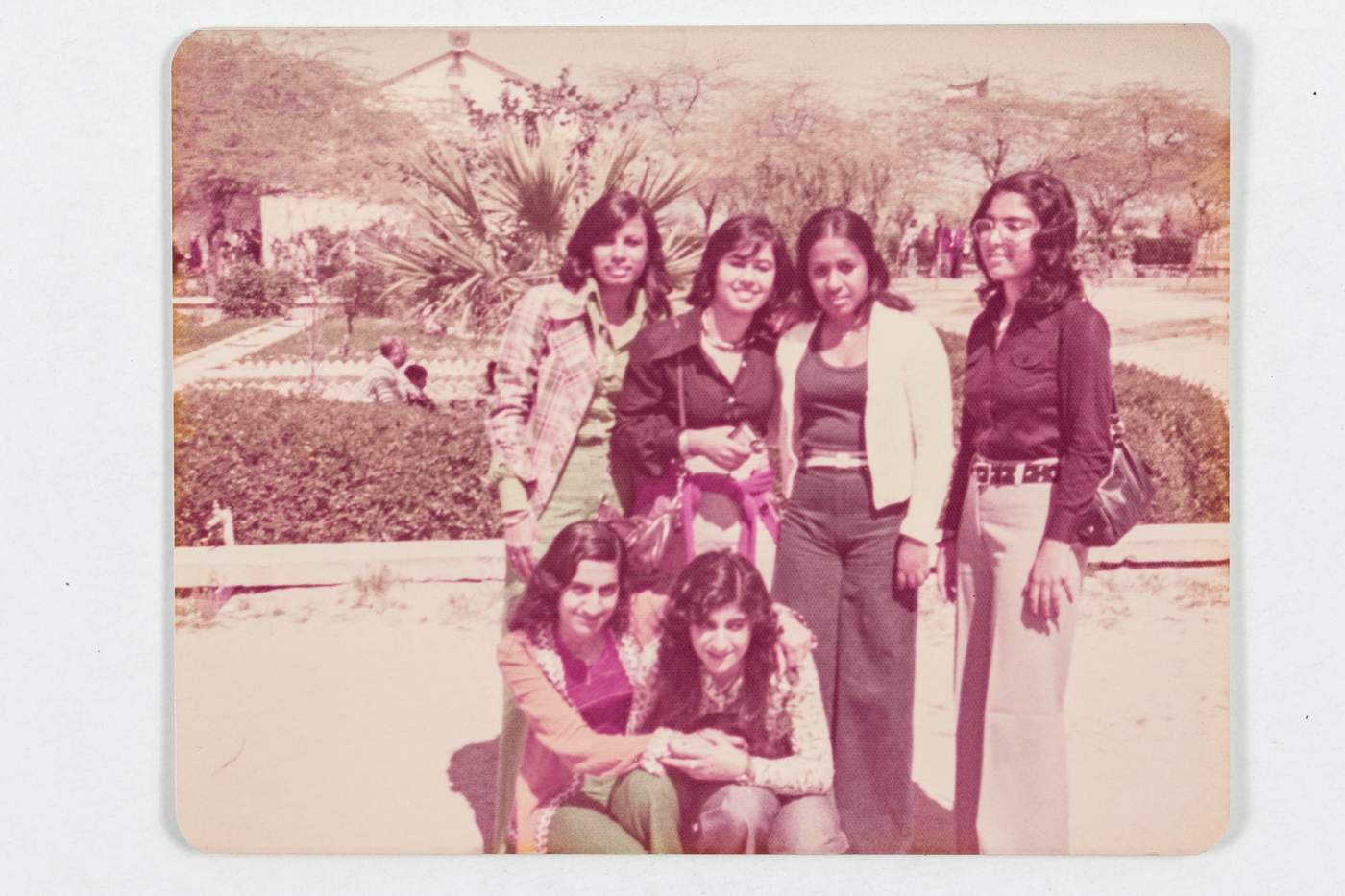

Shortly after, six women – also from Sharjah – enrolled in Kuwait University. By the early 1970s, 15 women from Dubai travelled to study abroad, and in 1976 the first woman from Abu Dhabi followed suit.

Today thousands of Emirati women travel across the globe to study – and they have those pioneering women to thank.

Mahfoudah Al Junnibi was the first Emirati woman from Abu Dhabi to seek an education abroad.

A few other girls would eventually join Ms Al Junnibi the same year, but the next batch to travel to Kuwait would be from the Northern Emirates.

Ms Al Junnibi speaks of challenging societal norms

In 1976, she was part of what she calls the “spoilt and pampered” generation.

Receiving 100 Kuwaiti dinars in allowance, with an entire building rented out for Emirati students and their own driver, she says she and her peers were inspired to work harder because of the Government’s support.

“We were pampered and had our own housing,” Ms Al Junnibi says. “The support of the Government was encouraging. We were well known at university as the girls from the UAE.

“We had our own bus with a designated driver, taking us to and from the campus and waiting for us until we finished classes. Every month someone from the embassy came to personally give us our allowance.

“We were so pampered and this support encouraged us to work as hard as we could.”

But like other young women, convincing her father to allow her to go was difficult.

“I was 16,” Ms Al Junnibi says. “It was a challenge. I’ll never forget my father’s face when he first took me to the university and he saw that it was co-ed.

“He met our cultural attache there and I’ll always remember my father telling him, ‘I’m entrusting you with my daughter. Take good care of her’.”

On her first day, Ms Al Junnibi overslept. “I was used to being woken up in the morning so I missed the exam that was responsible for determining my level and whether I’d be accepted into the programme or not. I woke up, quickly dressed and kept running all the way from the university to the college.”

Ms Al Junnibi talks about her first day at university

She made it to the exam on time and scored one of the top marks, but, she says, “it was a challenge for my father in allowing his daughter to travel alone at such a young age, with our culture and traditions that frown on women even leaving the house without a guardian.

“We used to only go from the school to the house and vice versa. I had to prove myself to my father and family and to make them all proud for their trust in me.”

Ms Al Junnibi graduated with honours and was the first Emirati social worker from Abu Dhabi. She worked at the Ministry of Education and was in charge of social workers for more than a decade.

She was also the first woman in her family to earn a bachelor’s degree.

“Women’s progression is not new but is a result of a strong foundation that took decades to form,” she says. “The building didn’t grow before the foundations were set.

“Our time was the hardest but while we were hearing about haram and taboos, our leadership was pushing us forwards and told us to go ahead.

“Support of the leadership is what let our parents approve that we move forward.

“What women have achieved in the West, Emirati women achieved a long time ago but it wasn’t easy and was a bigger struggle in our time than today.”

On Emirati Women’s Day, Ms Al Junnibi asks that women recognise each other’s efforts.

“I ask women today that when they are appointed or promoted to recognise that this is not the result of their achievements as individuals, but as a result of teamwork,” she says.

“Her success is not hers alone but the work of a team – whether it is the older generation or the younger. Without teamwork, she will not progress.”

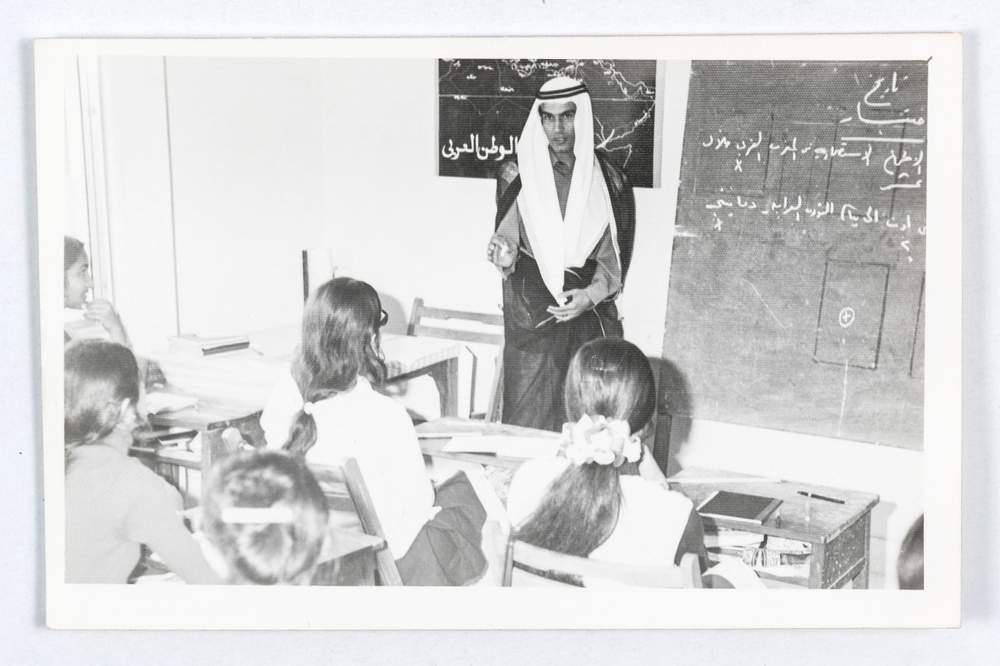

Dr Moza Ghobash began her education in the 1964 at the first semi-regular school established in Dubai – Al Ahmadiya, which has since been turned into a museum.

Al Ahmadiya School in Dubai, established in 1912.

“We were a small group of girls studying at the school, not more than six or seven,” Dr Ghobash says. “Then we moved to Khansa school in the ’70s and the number of students increased to about 20 girls.”

In 1973, she graduated from high school, ranking first across the country.

Afterwards her real struggle started, one she shared with the most ambitious women of her generation. She had to convince her family to let her travel abroad to continue her education. She was one of only 15 girls allowed to go to Kuwait University for their bachelor’s degree.

“It took me three months to convince my mother to allow me to go abroad to study,” Dr Ghobash says. “The geography played a strong part in determining where we went and it was an obstacle.”

The further the country, the more reluctant families were to allow their daughters to travel.

Dr Ghobash’s parents were intellectuals and often hosted poets, politicians and philosophers at their home.

“We had newspapers from Iraq and Syria come to us as gifts and an extensive library,” she says.

But still her parents were fearful of sending her abroad. “They finally agreed but my mother kept visiting for the entire year.”

Dr Ghobash calls her years in Kuwait a “new dawn”.

“It was daunting for all of 15 of us,” she says. “Our upbringing was very conservative and Kuwait University was very liberal. They had student unions and political groups as opposed to our completely closed society.

“We were careful and scared, with words like haram, your reputation and your family’s reputation ringing in our ears.”

The women also went on university-organised trips. One of Dr Ghobash’s most significant was to Kenya, which was not only the first time she and her fellow students had visited an African country but was also the first co-ed trip in which any of the girls had taken part.

Dr Ghobash and the 14 other Emiratis were placed in student dorms but the following year, the UAE rented out an entire building exclusively for young national women.

In 1977, she completed her bachelor’s degree in psychology and philosophy. When she returned, Sheikh Zayed, the Founding Father, had ordered the establishment of the country’s first university, UAE University in Al Ain.

Dr Ghobash was immediately hired as a teaching assistant but was soon packing her bags to travel for further education.

“I participated in the establishment of the university and was honoured to be tasked with supervising the female dorms,” she says. “In its first year, there were only 170 girls – now it’s almost 5,000.

“The speed of development of education in the UAE is astounding.

“Sheikh Zayed’s personal visits to the university showed families that he supported the education of girls.”

For her master’s degree Dr Ghobash chose to test her parents again but this time she chose a country further from home than Kuwait.

“When I came back to the UAE and wanted to study my master’s, my mother allowed me to go immediately to the US,” she says.

“So the choice of countries we were allowed to travel to reflected on how developed and accepting society was to an Emirati girl.

“I chose to travel and continue my education because I grew up knowing the importance of education and that the UAE’s development depended on it.”

She moved to Egypt, where she remained for seven years to complete her master’s and PhD. When she returned Dr Ghobash joined UAE University again, where she taught for 13 years. She wrote about 10 books and more than 50 research papers on the UAE.

She says that while she and her peers were viewed as trailblazers at the time, they were building on a long history of women’s education in the country.

“There are many great examples of educated women in the history of the UAE throughout the ’40s and ’50s and ’60s,” Dr Ghobash says.

“Sheikha Salama, mother of Sheikh Zayed, had an influential political role and Sheikha Latifa bint Hamdan, wife of Sheikh Rashid [bin Saeed Al Maktoum, then Ruler of Dubai] and my mother, and so many others.

“We had women in the ’40s who had educational majlises and judiciaries. They would open their majlis to resolve conflicts and offer counselling.”

Dr Ghobash speaks of the progress Emirati women have made

Dr Ghobash laments the lack of media coverage over the roles of the first Emirati women who shaped the future of the country, saying they deserved recognition for their achievements.

“When Dr Amal [Al Qubaisi, President of the FNC] and the young ministers were first appointed, many believed it symbolised development of Emirati women,” she says.

“They never acknowledged our role in making this possible. There is no tree without roots and this fruitful tree you see today, where do you think it came from?

“Nothing is created out of a vacuum. When I came from Kuwait, my main goal was to call for women’s education and after a while I started to call for women in the workforce, and later we called for women to be leaders.

“Who introduced these values other than my generation?”

On Emirati Women’s Day, while they are proud of the achievements of women today, Dr Ghobash and her peers want one thing – acknowledgment.

“This day was chosen two years ago,” she says. “It’s a beautiful day but let’s celebrate all the different women who have contributed to the women who have taken over the reins of leadership. Let’s celebrate those who have paved the way.

“While some saw the importance of the younger generation in being the new face of Emirati women, it should not be the face that covers the truth which is that this would not have been possible without my generation and the generation before me from as early as the 1950s.”

Credits

Words: Shireena Al Nowais

Photographs: Antonie Robertson, Satish Kumar, Dr Shafiqa Abbas, Dr Moza Ghobash, Paulo Vecina, Aysha Al Abusmait, Hessa Al Ossaily

Video: Andrew Scott

Editor: Juman Jarallah

Copyright: The National, Abu Dhabi, 2017