ONE YEAR OF PROTESTS.

AT LEAST 600 DEATHS.

LITTLE CHANGE IN IRAQ.

Years of corruption, unemployment

and poor governance

drove them to the streets

Live ammunition, tear gas

and kidnappings tried to push them back

12 months on, protesters have a new demand ...

Accountability

What has changed?

'A storm is coming': Iraqis use the anniversary to rekindle protest movement

Activists now demand the killers of demonstrators and corrupt officials be brought to justice, writes Sinan Mahmoud

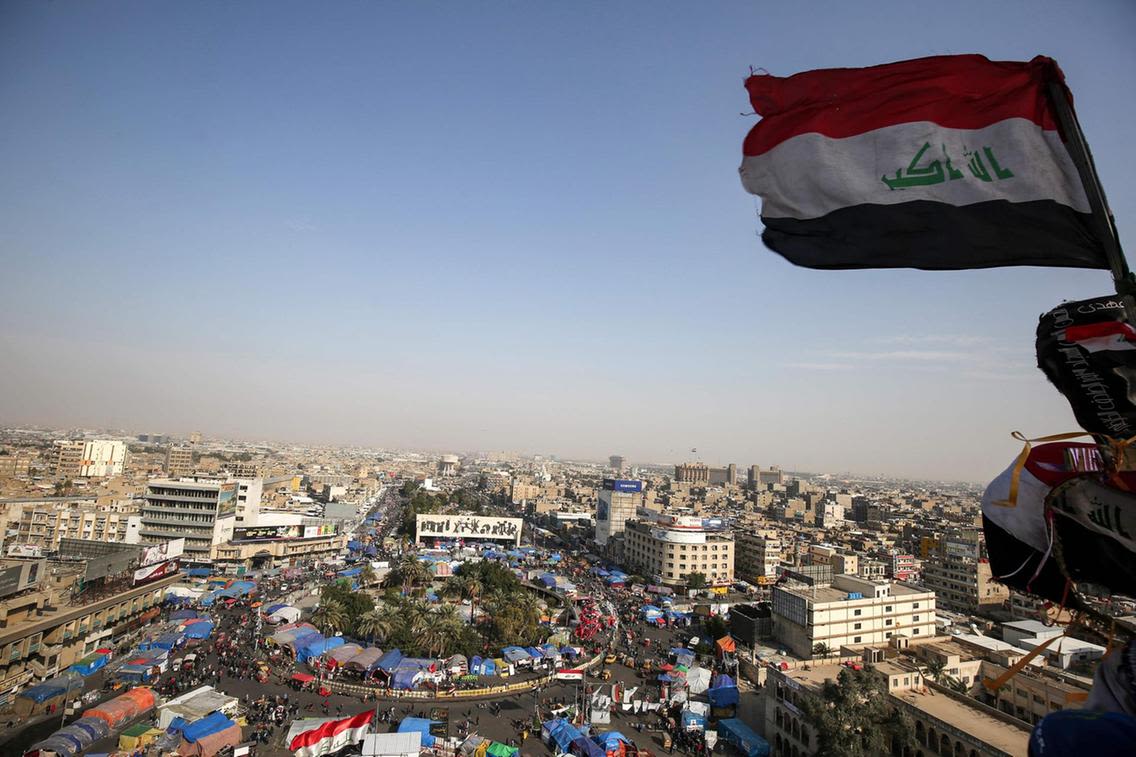

Under the unforgiving sun, volunteers sprayed water from hoses to scrub clean Baghdad's Tahrir Square.

Young artists touched up the murals, portraits and graffiti painted on an underpass near the square at the height of the pro-reform protests that broke out in Iraq last October.

Ahead of the first anniversary of the protests, they also added new artistic expressions of their frustration at the government.

Activists hope October 1 will help reignite the protest movement that died down in recent months because of the coronavirus pandemic and the killings, kidnappings and intimidation of protesters.

In addition to their original demands for better living conditions and political change, they say they are also pressing for those behind protesters' killings to be brought to justice.

“October is the date for the revolutionaries,” read one of many posters put up on Baghdad’s streets to encourage people to rejoin the movement.

“We will be back,” read another message scrawled on a wall in the southern city of Nasiriyah, another protest centre. “The storm of October is coming.”

Mustafa Abid next to a portrait of Safaa Al Sara, one of the symbols of the revolution. Haider Husseini for The National

Mustafa Abid next to a portrait of Safaa Al Sara, one of the symbols of the revolution. Haider Husseini for The National

Unlike other protests since the 2003 US-led invasion that toppled long-time dictator Saddam Hussein, these demonstrations started spontaneously.

Angry young people took to the streets in Baghdad before protest fever spread to other cities in central and southern Iraq.

The protesters demanded jobs, better services, an end to endemic corruption and an overhaul to the sectarian political party system in place since 2003.

They want early elections under a new law that gives independent candidates a better chance to win seats in Parliament.

Government security forces responded with live rounds, teargas and stun grenades, setting off clashes with the protesters.

At least 560 people, mostly protesters, have been killed, the government said. Thousands were wounded.

The government resigned weeks after the start of the protests.

A new government that took office in May has mooted June 2021 as a possible date for early elections, although discussions on changing the electoral law have not concluded.

“None of our demands are met yet,” activist Haider Al Hilfi told The National as he sat inside a tent in Tahrir Square.

“We will rise up again on October 1 in a new revolution."

Mustafa Abid paints a mural in Al Sadoon tunnel next to Baghdad's Tahrir Square. Haider Husseini for The National

Mustafa Abid paints a mural in Al Sadoon tunnel next to Baghdad's Tahrir Square. Haider Husseini for The National

For months, Baghdad’s Tahrir Square was a bustling centre for thousands of protesters who turned it into a vibrant village of tents filled with young men and women from all walks of life.

But things started to change early this year. Activists were attacked when outside the square, reportedly by Iran-backed militias.

Informants mingled with the protesters. Many abandoned the camp.

“People lost trust in the square when it was infiltrated by the political parties."

Days into the protests, the demonstrators took over the abandoned 14-storey Turkish Restaurant building from the security forces who oversee the Green Zone, where key government offices and western embassies are located.

The building became a landmark for the protest movement and was renamed Jabal Uhud, a reference to a mountain in Saudi Arabia where a historic battle took place.

Now the square is almost deserted, with many tents empty and torn.

“People lost trust in the square when it was infiltrated by the political parties,” says activist Mustafa Abid, who arrived on a motorcycle to check on anniversary preparations.

“But we managed to unify our ranks. We are now working in our areas and on social media to regain trust and muster people to come to the square to commemorate the anniversary.”

When he took office in May, Prime Minister Mustafa Al Kadhimi promised investigations into the killings of the protesters, and compensation for the dead and wounded.

The government's investigation is yet to begin. It says it will start soon after a list of the victims has been finalised.

No payments have been made and no charges filed so far.

“What hurts most is that we have achieved nothing despite the blood that has been shed."

Younis Khalifa, 23, burst into tears as he sat next to a section of the square where pictures of the dead are hung or placed on the ground, surrounded by their bloodstained belongings, copies of the Quran and plastic flowers.

“The people let down the protests,” Mr Khalifa says, expressing disdain for Iraqis who failed to back the movement when the killing began.

“What hurts most is that we have achieved nothing despite the blood that has been shed."

In the southern city of Basra, activist Sameer Rahim says as protests resume, so might the confrontations with security troops. But, he warned, there will be a response from the protesters.

"We expect heavy-handed response this time as well, but not the same one that we saw last year," Mr Rahim says.

"The government and political parties will think twice before firing a bullet because the protesters today are different, they will retaliate immediately the same way."

He expects the Basra protests will be bigger as they will be fuelled by an "alteration" of borders by neighbouring Kuwait, and a delay in building a major port on the Gulf.

Back in Tahrir Square, Mr Khalifa pledges to return on October 1.

“To those [who died] I say: 'We will not forget you and we will carry on'," even at risk of death.

Families of killed and wounded Iraqi protesters still waiting for justice

The government has promised a thorough investigation into the excessive use of force during protests that began last year, writes Sinan Mahmoud in Baghdad

Layla Abbas Hussein says a year has passed since the killing of her son, Mohammed, and there is still no clue about the killers. Haider Husseini for The National

For Layla Abbas Hussein, getting justice for her slain son seems a distant dream.

Mohammed Habib Abbas was the first demonstrator to fall in Iraq’s unprecedented pro-reforms protest movement. A tear gas canister fired by security forces lodged in his right shoulder and he bled to death.

“He was only holding the Iraqi flag and chanting ‘we want a country’ along with others,” Ms Hussein, 51, tells The National before bursting into tears.

“A year has passed now and there is no clue that could lead us to the killer, each government faction blames the other,” she says.

Ms Hussein's son Abbas, then 21, was one of the thousands of young people who took to the streets in Baghdad and southern cities.

The number of dead varies, but according to government statistics released on July 30, at least 560 protesters and members of security forces have been killed.

Most were protesters killed or wounded by security forces and state-backed militias firing live rounds and military-grade smoke or tear gas. But some were assassinated – including two young activists in Basra last month – or simply disappeared.

The government has failed to hold anyone accountable, promises of an investigation and financial aid remain elusive.

Ms Hussein says she is still devastated by the death of her son, who was to be married a few weeks later, and that a fire rages inside her.

Mohammed Abbas was 21 when he was killed. Haider Husseini for The National

“We have zero trust in the government to bring us justice,” she said.

“All I need now from the government is to identify the killer of my son and his tribe will take revenge.”

The government led by Adel Abdul Mahdi, which resigned over the violence, denied it had ordered the use of lethal ammunition against the protesters, blaming a “third party” for the killing.

This month, Mr Al Kadhimi, his replacement, announced that the first stage of listing the names of victims had been completed. The next stage involving the launch of investigations and bringing those involved to justice will start “soon”, he said.

Also this month, Iraq’s top Shiite cleric Grand Ayatollah Ali Al Sistani joined the calls for justice to the victims.

The government needs “to seriously work to reveal all those who committed criminal acts that killed and wounded protesters and security forces … especially parties that are behind kidnappings and assassinations," he said.

The government led by Adel Abdul Mahdi blamed a 'third party' for the killing. Haider Husseini for The National

Days later, Mr Al Kadhimi placed a travel ban on Iraqi army Lt Gen Jamil Al Shammari over his involvement in the deaths of dozens of protesters in the southern city of Nasiriyah in a single day last November.

The killings there were a major factor that led to the resignation of Mr Abdul Mahdi.

Thousands of protesters who survived their injuries are living with scars.

Haider Hassan Alwan was one of seven people who escaped with injuries when security forces opened fire on protesters in Baghdad’s Hafidh Al Gadhi square last November. Twenty others died.

Haider Hasan Alwan lost an eye during an attack on protestors. Haider Husseini for The National

But he also paid a price: the loss of his right eye.

“We were waving Iraqi flags and chanting slogans when security forces took us by surprise and attacked us from three directions,” Mr Alwan, 30, recalls.

“All of a sudden, a tear gas canister hit my forehead and penetrated about 2 centimetres, smashing the bone above my eye.”

Nearly two months ago, he lost his job driving a taxi when the car's owner took it back after an accident caused by his impaired vision.

“What hurts a lot is that we achieved nothing and the government doesn’t hold anyone accountable and doesn’t compensate us,” Mr Alwan says.

Mr Alwan has now lost his job as a taxi driver due to poor sight. Haider Husseini for The National

Desperate for justice, families have taken to social media to voice their complaints.

A mother launched a Facebook page dedicated to her son, Mohanad Al Qaisi, who was killed in February in the southern city of Najaf.

“We have been in the courts for seven months now and have offered the court evidence and witnesses, but to no avail,” the mother says in a video as she sits next to a picture of her son.

“I have not seen any of the committees that Mr Al Kadhimi formed and none called me… tell us what’s wrong with our case, why is it stalled?” she says.

Addressing the government, she adds: “If you don't see this case as a big one and you can’t proceed with it, tell us and I’ll go to the international courts.”

Layla Abbas Hussein says a year has passed since the killing of her son, Mohammed, and there is still no clue about the killers. Haider Husseini for The National

Layla Abbas Hussein says a year has passed since the killing of her son, Mohammed, and there is still no clue about the killers. Haider Husseini for The National

Mohammed Abbas was 21 when he was killed. Haider Husseini for The National

Mohammed Abbas was 21 when he was killed. Haider Husseini for The National

The government led by Adel Abdul Mahdi blamed a 'third party' for the killing. Haider Husseini for The National

The government led by Adel Abdul Mahdi blamed a 'third party' for the killing. Haider Husseini for The National

Haider Hasan Alwan lost an eye during an attack on protestors. Haider Husseini for The National

Haider Hasan Alwan lost an eye during an attack on protestors. Haider Husseini for The National

Mr Alwan has now lost his job as a taxi driver due to poor sight. Haider Husseini for The National

Mr Alwan has now lost his job as a taxi driver due to poor sight. Haider Husseini for The National

Iraqi civil activist Fahim Al Tai. Reuters

Iraqi civil activist Fahim Al Tai. Reuters

Karrar Adil. Courtesy Ghofran Al Noori / Facebook

Karrar Adil. Courtesy Ghofran Al Noori / Facebook

Ahmad Abdessamad and Safaa Ghali. AFP

Ahmad Abdessamad and Safaa Ghali. AFP

Iraqi activist Riham Yakoub. AFP

Iraqi activist Riham Yakoub. AFP

ISIS terror expert Husham Al Hashemi. AFP

ISIS terror expert Husham Al Hashemi. AFP

Tahseen Oussama Al Khafaji. @OussamaTahseen via Twitter

Tahseen Oussama Al Khafaji. @OussamaTahseen via Twitter

The mural of Safaa Al Saray. AFP

The mural of Safaa Al Saray. AFP

Abdul Quddus Qasim. Courtesy Facebook

Abdul Quddus Qasim. Courtesy Facebook

The bullets and batons were fired indiscriminately but of the at least 560 killed, many were singled out and murdered.

Here are the stories of some of the most well-known figures in the movement and other high-profile Iraqi figures killed since last October:

Safaa Al Saray

The engineering graduate, 26, became the face of Iraq's anti-government movement after he was shot in the head by a tear gas canister last October.

He died from injuries shortly after.

Al Saray’s murals are found around Tahrir square, the centre of Baghdad's rallies.

He was a poet and activist whose main focus was to promote civil and political rights in the country.

Al Saray was an active participant of Iraqi protests, he took part in the anti-corruption demonstrations in 2011, 2013 and 2015.

Husham Al Hashimi

Ahmad Al Rubaye / AFP

Ahmad Al Rubaye / AFP

Husham Al Hashimi, 47, is perhaps the most well-known figure killed since last year. The Iraqi political and security expert was shot dead at point-blank range by unknown assailants as he parked his car outside his house on July 7.

While he was not an activist in the protest movement, he was working closely with Mr Al Khadimi and was a member of the Iraq Advisory Council, a panel of prominent experts and former policymakers.

He was strongly in favour of the popular protests and sought a strong competent state.

The brutal murder of one of Iraq's most prominent experts on ISIS, militias and security sent shockwaves around the world and was interpreted by many as a direct challenge to the Mr Al Kadhimi's government’s pledges to rein in armed militias.

Ahmed Abdul Samad and Safaa Ghali

Samad, 39, was a correspondent for the local television station Al Dijla. He was shot dead while working along with his cameraman Ghali, 26, in Basra in January.

The two were covering the government crackdown on the country’s mass protests, documenting the arrests of anti-government demonstrators in the oil-rich southern city.

Tahseen Oussama Al Khafaji

A well-known activist who was shot several times on August 14 after unknown gunmen broke into his internet service company in Basra.

Al Khafaji had taken part in the anti-government protests that rocked the country since last October.

His death triggered protests in the city, demanding accountability for the government’s inaction to protect civilians. It led to the killing of Ms Yakoub who also took part in the protests.

Before he was killed, he had posted a note on Facebook that he received from his daughter urging him not to go out and protest.

Al Khafaji responded to her in the post and said: “If we do not stand up to them [the political class] now, then no-one will ever try to overthrow them. This is our chance, we must not waste it.”

Riham Yakoub

Alaa Al Marjani / Reuters

Alaa Al Marjani / Reuters

The civil society activist, 30, was murdered by gunmen on August 19 in the southern city of Basra.

Her death sparked more public outrage at the government.

Ms Yakoub was a graduate in sports science who ran a women’s health and fitness centre in Basra.

The bullets and teargas were fired indiscriminately but of the at least 560 killed, many were singled out and murdered.

Here are the stories of some of the most well-known figures in the movement and other high-profile Iraqi figures killed since last October:

Safaa Al Saray

The engineering graduate, 26, became the face of Iraq's anti-government movement after he was shot in the head by a tear gas canister last October.

He died from injuries shortly after.

Al Saray’s murals are found around Tahrir square, the epicentre of Baghdad's rallies.

He was a poet and activist whose main focus was to promote civil and political rights in the country.

Al Saray was an active participant of Iraqi protests, he took part in the anti-corruption demonstrations in 2011, 2013 and 2015.

Husham Al Hashimi

Ahmad Al Rubaye / AFP

Ahmad Al Rubaye / AFP

Husham Al Hashimi, 47, is perhaps the most well-known figure killed since last year. The Iraqi political and security expert was shot dead at point-blank range by unknown assailants as he parked his car outside his house on July 7.

While he was not an activist in the protest movement, he was working closely with Mr Al Khadimi and was a member of the Iraq Advisory Council, a panel of prominent experts and former policymakers.

He was strongly in favour of the popular protests and sought a strong competent state.

The brutal murder of one of Iraq's most prominent experts on ISIS, militias and security sent shockwaves around the world and was interpreted by many as a direct challenge to the Mr Al Kadhimi's government’s pledges to rein in armed militias.

Ahmed Abdul Samad and Safaa Ghali

Samad, 39, was a correspondent for the local television station Al Dijla. He was shot dead while working along with his cameraman Ghali, 26, in Basra in January.

The two were covering the government crackdown on the country’s mass protests, documenting the arrests of anti-government demonstrators in the oil-rich southern city.

Tahseen Oussama Al Khafaji

A well-known activist who was shot several times on August 14 after unknown gunmen broke into his internet service company in Basra.

Al Khafaji had taken part in the anti-government protests that rocked the country since last October.

His death triggered protests in the city, demanding accountability for the government’s inaction to protect civilians. It led to the killing of Ms Yakoub who also took part in the protests.

Before he was killed, he had posted a note on Facebook that he received from his daughter urging him not to go out and protest.

Al Khafaji responded to her in the post and said: “If we do not stand up to them [the political class] now, then no-one will ever try to overthrow them. This is our chance, we must not waste it.”

Riham Yakoub

Alaa Al Marjani / Reuters

Alaa Al Marjani / Reuters

The civil society activist, 30, was murdered by gunmen on 19 August in the southern city of Basra.

Her death sparked more public outrage at the government.

Ms Yakoub was a graduate in sports science who ran a women’s health and fitness centre in Basra.

Karrar Adil and Abdul Quddus Qasim

Adil, a lawyer from the southern governorate of Maysan, was shot dead in May alongside his friend, anti-government activist, Qasim, by unknown gunmen.

Their families blame the government for their brutal murder.

Fahem Al Tai

Abdullah Dhiaa Al Deen / Reuters

Abdullah Dhiaa Al Deen / Reuters

A civil society activist, Al Tai was shot dead in the holy city of Karbala in Iraq's south while returning home from anti-government protests last December.

Al Tai, 53, had been taking part in weeks of rallies denouncing Iraq’s entrenched political elite as corrupt, inept and beholden to neighbouring Iran.

Al Tai, who was married with children, had been publicly critical of other intimidation attempts against protesters.

“We will be victorious and our country will return, despite you. Despite the pain inside us, we will smile. Despite you, despite your rotten parties,” he wrote on Facebook less than a day before he died.

Zahra Ali

Her bruised body was left outside her family home in Baghdad, hours after she had gone missing.

Ali, 19, was a university student who played no part in politics, her family told local media.

"Zahra often spent the money I gave her on the demonstrators to help her colleagues," her father Salman Ali said. "She was a good, peaceful person who only wanted to help others,” he added.

“My daughter was killed because she supported her colleagues," The family, he said, did not receive any death threats.

Ali Al Lami

Al Lami, 49, was found dead last December with gunshot wounds to the head.

From Kut, he had arrived in Baghdad days earlier to join the protests with his children.

The father of five had called on social media for protesters to march peacefully.

Police claim his attackers had used silencers and forensic experts said had been shot three times.

"It was the militias of a corrupt government that killed him," his close friend Tayssir Al Atabi said.

Broken but unbowed: The life-changing injuries of Iraq’s revolution

These are stories of those vowing to carry on despite wounds that will last a lifetime, writes Gareth Browne in Baghdad

Seif Salman awaits a physiotherapist for treatment ahead of having a prosthetic leg fitted. Ameer Hazim for The National

Seif Salman awaits a physiotherapist for treatment ahead of having a prosthetic leg fitted. Ameer Hazim for The National

As he hopped into a treatment room, the denim below Seif Salman’s right knee flaps where his leg used to be.

He is just one of the thousands of young Iraqis who took to the front lines of the protests.

“I didn’t see the shot, but I heard it,” he tells The National. “I hit the ground before I saw what had happened to my leg.”

He unflinchingly relived the moment through a grainy video on his phone. A tear gas canister continues to pump out plumes of smoke, though it is lodged below his knee. Another protester wrapped a flag around the wound, a feeble attempt at a tourniquet. Without emotion, he watched himself writhe in pain.

Seif Salman has been receiving physio to strengthen his thighs after having his right leg amputated. Ameer Hazim for The National

Seif Salman has been receiving physio to strengthen his thighs after having his right leg amputated. Ameer Hazim for The National

Unshaven and stocky, Mr Salman is now receiving treatment at the Baghdad Medical Rehabilitation Centre, a clinic run by Medecins Sans Frontiers. His leg was amputated, though he insisted his wound has done nothing to dampen his spirit.

Soon he will be fitted with a prosthetic limb, and after that, he says, he has no doubt he will return to Tahrir Square.

Activists accuse security forces of intentionally firing tear gas canisters at protesters’ bodies, and a slew of pictures on social media and WhatsApp groups show canisters embedded in the various limbs of maimed protesters.

Others hit in the face or head have not been as lucky as Mr Salman.

As well as the at least 560 killed since last October, in the first four months of protests alone around 24,000 were wounded.

Literally thousands of young Iraqis are now living with similar life-changing injuries to Mr Salman.

Yet, while the deaths of activists and protesters grab headlines and social media outrage – those who have had their lives altered dramatically are left to fend for themselves. But some have returned to the squares of the cities, picking up their protest once more, as though nothing has ever happened.

Mr Salman had travelled to Baghdad that November day to join the protests from his home in Hillah on a branch of the Euphrates, about 120 kilometres south of the capital. He turned off his phone and told his family he was visiting a friend.

He describes the euphoria of first walking into Baghdad’s Tahrir Square. “The square was everything Iraq could be,” he said.

He was part of a small group on the front lines, tasked with dealing with tear gas. They ran towards the gas canisters, smothered them in blankets, or tossed them away.

It was dangerous, often taking them into the crosshairs of security forces.

Dr Saad Suleiman describes treating a 'gush' of patients when protests reached their peak in November. Ameer Hazim for The National

Dr Saad Suleiman describes treating a 'gush' of patients when protests reached their peak in November. Ameer Hazim for The National

Dr Saad Seleiman, 29, is one of the clinic’s doctors. As the violence peaked in October, he was part of a team running a clinic close to the action.

“It was a gush of patients coming at once, many injured patients, multiple areas... I was even choking from the smoke,” he recalls.

“Patients were afraid to be admitted to public hospitals, they feared being arrested."

Physiotherapist Ashar Hassan attempts to desensitise Seif Salman's stump. Without these exercises, he may be unable to use a prosthetic leg. Ameer Hazim for The National

Physiotherapist Ashar Hassan attempts to desensitise Seif Salman's stump. Without these exercises, he may be unable to use a prosthetic leg. Ameer Hazim for The National

Since protests began, he says he has seen everything from gunshots wounds to amputations like Mr Salman's being carried out.

“I saw patients with live bullets, some of them had brain injuries, they had gunshots in their head, and in the abdomen, of course,” he recalls.

Outside, Mr Salman teases another patient – Ali Salem Jassem, 21, a tuk-tuk driver from Sadr City.

Ali Salam Jassem describes is leg as hanging 'like a feather' after being shot during protests late last year. Ameer Hazim for The National

Ali Salam Jassem describes is leg as hanging 'like a feather' after being shot during protests late last year. Ameer Hazim for The National

His simple life ferrying shoppers around was upturned when protests broke out.

Tuk-tuks became the ambulances of the front lines and a symbol of the revolution more widely.

Mr Jassem remembers the night of November 7 well. As he sped towards the clashes, searching for those in need of help, he leapt from his Tuk-tuk to aid a man and heard a bang.

“My leg went all the way back,” he says, tracing a scar with his hand as he held a cigarette. “It was like a feather, it was just dangling”.

His thigh is marked, front and back, the entry and exit wounds.

Ali Salam Jassem shows of the exit wounds for gunshots he was hit by during the protests last year. Ameer Hazim for The National

Ali Salam Jassem shows of the exit wounds for gunshots he was hit by during the protests last year. Ameer Hazim for The National

Were it not for the treatment received at the field hospitals, he too might have lost a leg. But he shrugs it off. Just two days after being discharged, he hobbled back to Tahrir on crutches.

Looking at the scars on his thigh, Mr Jessem could be forgiven for a harbouring hatred toward those who shot at him. But his anger, he insists, is at Iraq’s failing institutions, and those who lead them, not the government’s foot soldiers.

“The person holding a gun doesn’t know my intention,” he says.

“Maybe the guy who shot me was afraid."

* This story was first published in The National on January 18, 2020

How violent repression and Covid-19

may still kill the uprising

Demonstrators vow to carry on until the government meets their demands but numbers are reducing on the streets, Mina Aldroubi reports

Iraqi women seen at anti-government protests in the holy city of Najaf on October 30, 2019. AFP

A year in, Iraq’s protest movement has yet to achieve its aim of wholesale political change and risks being snuffed out by widespread violence and intimidation at the hands of the security forces and militias coupled. The Covid-19 pandemic, experts and activists say, has only made things worse.

The protestors demand the replacement of the political system that has left public services crumbling and overseen the rise of overwhelming corruption.

While the movement – and ultimately, the violence that faced it – forced the resignation of prime minister Abdul Mahdi, nothing systemic has changed.

“Not much has changed, accountability for those killed have not been made, electoral law has not changed in the way we would have hoped, we wanted to put an end to the sectarian divides in parliament. We’ve not seen any deep-rooted changes,” Inas Jabbar, a human-rights activist from Baghdad told The National.

Protesters gather on Al Jumhuriya Bridge which leads to the Green Zone in Baghdad on October 31, 2019. AFP

While protesters managed to maintain momentum in the face of bullets and teargas, by the time the global pandemic forced the government to order people to stay home in mid-March, momentum was waning.

“There is a willingness from the public to re-engage in the movement, but threats, assassinations and coronavirus have impacted and reduced its momentum,” Ms Jabber said.

She participated in last year's protests and said ahead of the anniversary that demonstrators would be back in Tahrir Square because the government has not met their demands.

Protesters called for sweeping changes to Iraq's political system, put in place after the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq.

The May election of Mr Al Kadhimi, who said he wants to implement the changes demanded on the streets and hold early elections, broke the political deadlock.

But, experts warn that he will not be able to deliver the systemic shift many on the street want to see.

An Iraqi women uses a sling to hurl rocks at security forces on Al Rasheed Street, Baghdad, on November 29, 2019. Getty Images

“The Iraqi situation is beyond a place where incremental reform could work,” said Renad Mansour, senior researcher and Iraq expert at the Chatham House in London.

Neither the government nor political parties have been able to respond to the public’s needs, so Iraqis will continue to protest he said.

“They haven’t addressed the roots of the Iraqi state that these protesters are rising up against. So, until they are addressed, changing a person or a post here or there, won't work,” Mr Mansour told The National.

While the demands on the street are numerous, one issue that highlights the difficulty Mr Al Kadhimi faces is in compensating the families of protesters killed or wounded or prosecuting officers responsible.

“The government has not even compensated those injured by security forces, there has been little contact made with them,” Ms Jabbar said.

Delivering accountability is even more of a challenge because those responsible are protected by the security forces or have powerful political cover, Lahib Higel, Crisis Group's senior analyst for Iraq, told The National.

Such has been the crackdown and internal divisions, the expert says it is unlikely Iraq will see demonstrations on the scale of the peak of the movement.

“One reason is that protesters have different visions for how to carry on the struggle. Another is the violence and intimidation that many mobilisers have faced,” she said.

But Belkis Wille, a senior crisis and conflict researcher at Human Rights Watch, said protesters today have an even more reason to take to the streets than they did a year ago. While the movement was initially powered by anger at the system’s failings, there is now the anger at the killing of demonstrators and the government's inability to hold the perpetrators to account while still failing to pass reforms.

Iraqi students take part in an anti-government demonstration in front of their university in Basra on October 29, 2019. AFP

“The question is going to be whether this government is able to control the security forces across the country and ensure respect for the protesters' safety. And we don't yet know the answer to that,” Ms Wille said.

While the pandemic and violence appeared to reduce the numbers taking to the streets each week, Toby Dodge, an Iraq expert at the London School of Economics, told The National, said that the protests have already returned but are more geographically diffused across the south and no longer centrally focused on downtown Baghdad.

“They could well explode again ... But they are not yet as strong as last year because of the sustained, mostly covert, violent repression delivered by the militias,” he said.

This campaign of repression has broken up the protest leadership but, along with Covid-19, has also discouraged all but the most tenacious from taking to the streets, Mr Dodge said.

A young Iraqi is tossed into the air by fellow demonstrators during a lighter moment in the protests in Tahrir Square, Baghdad, on December 3, 2019. AFP

Raid Madhaa, a protester whose murals in Tahrir Square became a symbol of the protests, said the demonstrations started to disintegrate in February following the outbreak of coronavirus and was derailed by infiltrators.

“They really ruined the movement, a friend of mine was going to get killed because of the infiltrators. People are in two minds when it comes to participating this year – they are worried about their safety and feel that their voices are not heard,” Mr Madhaa told The National.

“I’ll be there on Thursday, but will be monitoring the situation from far away because there is a lot of uncertainty as to what will happen this week,” he said.

Iraqi students take part in an anti-government demonstration in front of their university in Basra on October 29, 2019. AFP

Iraqi students take part in an anti-government demonstration in front of their university in Basra on October 29, 2019. AFP

Iraqi women seen at anti-government protests in the holy city of Najaf on October 30, 2019. AFP

Iraqi women seen at anti-government protests in the holy city of Najaf on October 30, 2019. AFP

Protesters gather on Al Jumhuriya Bridge which leads to the Green Zone in Baghdad on October 31, 2019. AFP

Protesters gather on Al Jumhuriya Bridge which leads to the Green Zone in Baghdad on October 31, 2019. AFP

An Iraqi women uses a sling to hurl rocks at security forces on Al Rasheed Street, Baghdad, on November 29, 2019. Getty Images

An Iraqi women uses a sling to hurl rocks at security forces on Al Rasheed Street, Baghdad, on November 29, 2019. Getty Images

A young Iraqi is tossed into the air by fellow demonstrators during a lighter moment in the protests in Tahrir Square, Baghdad, on December 3, 2019. AFP

A young Iraqi is tossed into the air by fellow demonstrators during a lighter moment in the protests in Tahrir Square, Baghdad, on December 3, 2019. AFP

Credits

Words: Sinan Mahmoud;

Mina Aldroubi; Gareth Browne

Photographs: Haider Husseini for The National; Ameer Hazim for The National; AFP Photo; Reuters; Getty Images

Videography: Suhail Rather; Aneesh Grigary; Mina Aldroubi

Producer: Stephen Nelmes

Editors: James Haines-Young; Taylor Heyman; Russel Murray; Erica Elkhershi; Olivia Cuthbert; Joe Jenkins; Mary Gayan

Copyright The National, Abu Dhabi, 2020