The internal combustion engine is facing a watershed moment; major manufacturer Volvo will stop producing petroleum-powered vehicles by 2021, and countries in Europe, including the UK, have vowed to ban their sale before 2040.

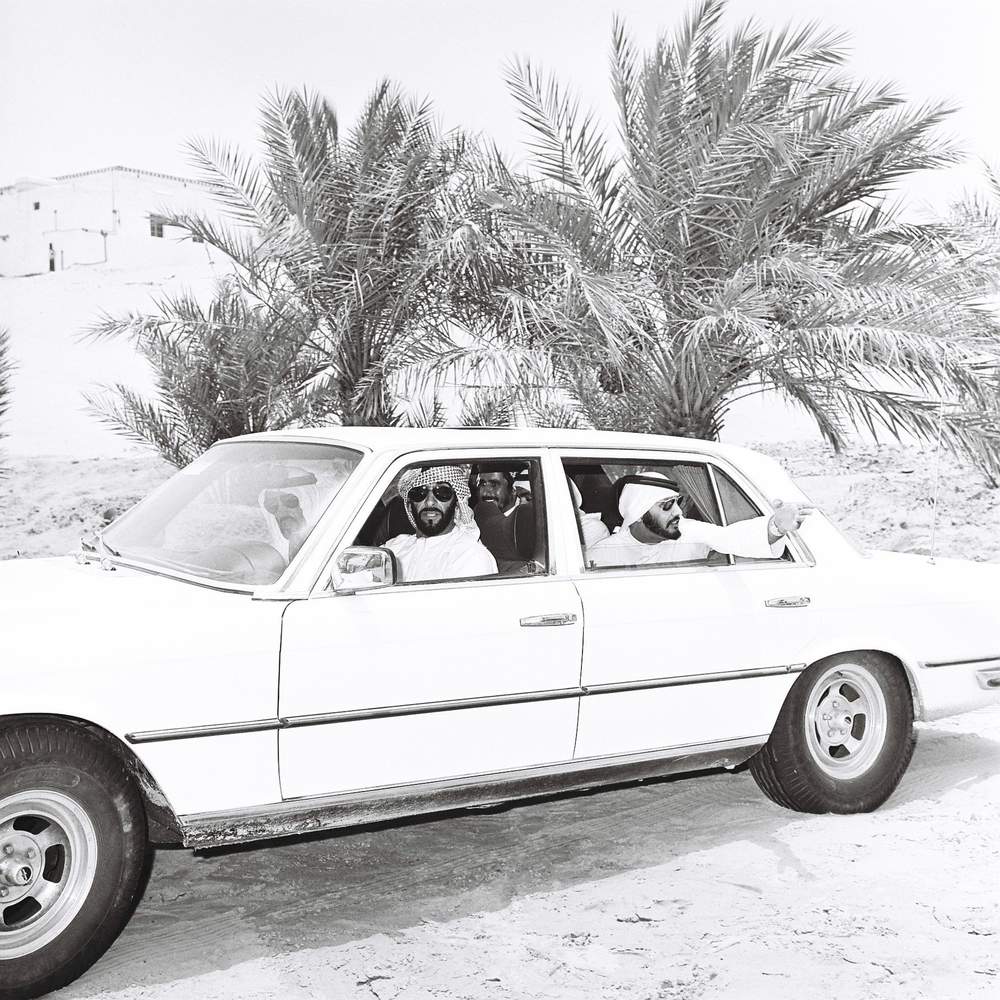

We take a look at the story of one of the most successful technologies of the past 100 years, and how it has impacted life in the United Arab Emirates.

The adoption of the internal combustion engine, a revolutionary invention that took the power of the steam locomotive and made it more compact and convenient, saw horse-drawn carriages move from the streets to the history books within 15 years.

Enormous fortunes were made, everyday life was transformed and cityscapes were reimagined.

Now, almost a century after the first Model T rolled off Henry Ford’s assembly line, the race is on to find an alternative power source to battle the global emissions crisis – the unforeseen legacy of the internal combustion engine and a testament to the ubiquitousness of the technology.

The world has changed dramatically over the past 100 years, and will continue to do so.

In 1913, the world’s population was around 1.8 billion.

Today, it stands at 7.6 billion. By 2050, it is expected to surpass 9 billion, and the International Energy Agency has estimated the number of cars will double from the current figure of 1 billion.

The UN expects the global population to exceed 11 billion by the end of the century.

Rising numbers of people means rising demand for energy, which, unless something dramatically changes, will ensure the world misses its target of limiting the global temperature rise to 2°C above pre-industrial levels.

With the transport sector accounting for more than a quarter of total world energy use, many governments are turning their attention to lowering vehicle emissions.

The EU has set a 2050 target for reducing emissions from the transport sector by 95 per cent. Countries including Britain, China and France have announced plans to phase out the sale of petrol and diesel engines within the next few decades.

India wants all its vehicles to be electric by 2030.

Prof Paul Ekins, co-director of the UK Energy Research Centre, said that unlike other carbon-heavy industries such as the building sector, the hyper-competitive automobile industry has willingly committed in recent years to finding an alternative, low-carbon model.

“The mood music was changing and they couldn’t afford to allow things to happen without them.

“They would rather be inside the tent influencing the direction than outside the tent and trying to knock it down,” said Prof Ekins, also of University College London’s department of resources and environment policy.

He is convinced this move away from the internal combustion engine has been driven largely by climate change, followed by more awareness of local air pollution issues and the Volkswagen emissions scandal.

“The thing that has changed above all is that the narrative around low-carbon technology has changed,” Prof Ekins said.

“If you go back to the Copenhagen conference in 2009, all the talk was about burdens and cost sharing and who was going to do it. “Well, politics doesn’t deal well with that kind of narrative.

“In Paris [in 2016], all the talk was about opportunity: ‘we have new technology’, ‘we have innovation’, ‘this is going to be one of the defining areas of competitive advantage in the future’.

“This is something that was started by climate change more than anything else and I think that it was pushed by the perception of technological opportunity, and it’s now effectively unstoppable.”

The challenge of finding low or zero-emissions energy for vehicles that can still deliver speed, distance, comfort and status is a difficult one, but it is something the industry has realised it must do to maintain market share.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, electric vehicles powered by batteries almost became the dominant technology, but fell out of favour because of the impracticality of how often they needed to be recharged.

Research into batteries never stopped, but only in recent years has the technology seemed viable for automobiles.

This comes at a time when the general appeal of an electric vehicle has increased, said Dr Anna Bonne from the UK’s Institution of Engineering and Technology.

“The image of the electric vehicle has changed from the tiny short-range commuter car to a luxury vehicle,” Dr Bonne said.

“Tesla has made the electric vehicle market sexier by designing one you would actually like to drive. Audi, Porsche, Jaguar Land Rover and Aston Martin have all announced that they will be producing electric vehicles soon.”

The other challenge facing the increased adoption of electric vehicles is where the energy powering the batteries will come from. In the UK, with a population of 65.6 million, it is predicted that demand will grow from the current 336 terawatt hours a year by about 20 per cent over the next 20 years. By 2050, demand is expected to be 520 TWh/year.

“The main challenge from the climate change point of view is to get low-carbon electricity, because at the moment electric cars emit just as much carbon as internal combustion engines. It’s just emitted at the power station and not from the car,” Prof Ekins said.

There are a number of solutions to the emissions problem, such as biofuels, and one leading contender is nuclear energy.

Speaking at a recent event, Harry Holt, president of Rolls-Royce Nuclear, said that to keep up with demand, low-carbon power generation would need to increase threefold.

Last year, Mr Holt’s company produced 150 TWh of low-carbon energy.

By 2030, they are aiming to produce 350 TWh, and by 2040 that will rise to 425 TWh.

“What that means as a challenge to the industry is we’re going to need to install about 95, just short of 100, gigawatts of electricity generating capacity by 2035, which is effectively replacing the entirety of what we’ve got and a little bit more on top of that,” he said.

Mr Holt believes nuclear will need to provide about 28 per cent of the installed energy capacity in 2050.

To do this, Rolls-Royce Nuclear is investing in small-scale nuclear reactors.

“We believe that these small modular reactors are going to have a very high load factor, a very high rate of utilisation,” Mr Holt said. “We believe they are quicker and easier to build and they therefore significantly reduce the financing burden and ultimately provide competitive electricity to the market.”

The other environmental factor to be considered with widespread battery adoption is the social-environmental one. The resources used in batteries are incredibly valuable.

Tesla plans to sell 500,000 electric cars a year. Using current technology, the company would need about two thirds of the world’s annual lithium production for their batteries. Supplies of other minerals such as cobalt could also come under pressure.

Although this means they are unlikely to be thrown away and therefore the risk of batteries ending up in rivers or landfills is low, it does mean the areas of the world where lithium is mined will be under pressure.

Despite the challenges, just as there was with the development of the internal combustion engine, large sums of money are there to be made.

As highlighted in the UK’s Clean Growth Strategy, analysis for the UK Committee on Climate Change estimated the low-carbon economy has the potential to grow 11 per cent per year between 2015 and 2030 – four times faster than the rest of the economy.

More than £2.5 billion (Dh12.44bn) will be invested by the UK government between 2015 to 2021. This forms part of the largest increase in public spending on UK science, research and innovation in almost 40 years.