The scourge of maritime robbery and hostage-taking is back. Somalia’s natural and economic catastrophes including soaring unemployment for young men have combined to leave youths vulnerable to the call to arms from the region’s resurgent pirates. Ramola Talwar Badam explores how this happened – and what can be done to counter the threats to shipping trade and the families of sailors who could be the next ones to be taken hostage.

Four months after his ship was freed from pirates, a Sri Lankan sailor plans to return to sea next month.

Now, Sunil Bulathsinhala just wants to forget the four days of terror he endured beginning March 13, when gun wielding Somali pirates held eight sailors hostage aboard the Aris 13, a UAE-managed tanker, marking the first successful hijacking after a five-year lull.

“I try to forget how many guns they had, how they held a gun to my head and made me talk to my family to ask for money. They had AK47s, T56, T81 (assault rifles), small rocket-propelled grenades and 9mm pistols,” said Mr Bulathsinhala from his Colombo home.

“I thought I would die. I tried to forget this. My mind is okay now. I am tough. I cannot be scared when I go back to work.”

A group of six pirates pretending to be fishermen first boarded the slow-moving bunker barge that was travelling from Djibouti to Mogadishu. Thirty armed pirates later clambered aboard. Working 12-hour shifts, they stripped the tanker of equipment and food.

“They took our phones, laptops, everything. I had only two tee-shirts and shorts. They took two motorboats, life jackets and the radio. They used big garbage bags to take away water, rice, soup cans, Pepsi and spaghetti.”

The Aris 13 which was hijacked on March 13. Kevin Finnigan / AP

Mr Bulathsinhala says he cannot block out the terrifying exchange of gunfire during the March 16 rescue by the Puntland Maritime Police Force and the Bosaso Port Police, also in Puntland, a semi-autonomous state in Somalia.

“My heart pained during the shooting. The bullets were over us, we were in the middle. I still hear the sound. I have never been so afraid.”

Samudra Hettarachchi, Sunil’s wife, said sailors were vulnerable. “If the route is changed and they have to go near Somalia, the crew cannot do anything. They want to earn, so they will obey. But companies should not send them to unsafe places. If something happens to them, what will happen to us? When the ship was hijacked I was only thinking of the end. I was thinking how we will manage the rest of life.”

Being the sole breadwinner with a daughter to support through university, Mr Bulathsinhala, 57, says he has no choice but to return to sea. “I need work. We need the money.”

But he won't go back on just any ship. “A big ship with more speed, barbed wire and at least 4-6 guards on lookout,” he said, detailing the minimum security he wants before signing on.

Still, despite his fears and concerns, he also says he understands why some Somalis turn to piracy. Having lived in Fujairah and working in the Gulf gave him some Arabic abilities. He was thus able to function as a stand-in interpreter initially for the pirates. “I understood some Arabic, so I helped translate until the main interpreter came on board who spoke very good English. They would talk about how their country had too many problems, how 80 per cent of the livestock is dead, how they had no rain for many years. They are poor and so they are thieves.” This narrative of drought, unemployment and lawlessness as a trigger for piracy is one acknowledged by aid groups.

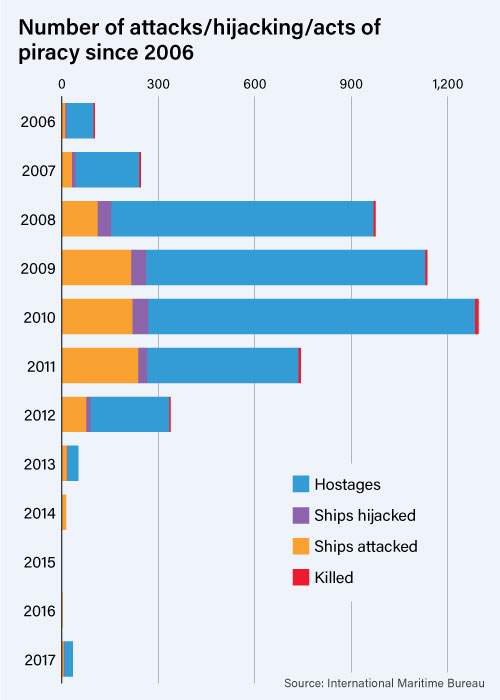

For years, the growth of Somali piracy was relentless. More people were taken hostage at sea in 2010 than in any year since the International Maritime Bureau began keeping records in 1991. Pirates captured 1,016 seafarers and killed eight; 49 ships were hijacked following a total of 219 attacks.

Since 2006, when attacks began to rise sharply, more than 29 crew have been killed. The incidence of piracy peaked in 2011, when 237 ships were attacked.

A combination of patrols by international navies and tighter security measures on merchant vessels gradually beat back attacks. It was after a five-year respite that the Aris 13 was hijacked, followed on March 21 by Al Kausar dhow, loaded with rice and wheat enroute from Dubai to Yemen. Ten Indian sailors were released by Somali forces after 10 days in captivity.

Omer Jama Farah, director and founder of the Taakulo Somali Community, an aid organisation working with marginalised groups, said the problem was worsening. “There has been a cholera outbreak and people are also suffering due to severe drought with most of the livestock dead,” he said.

“We received some rain, but that will not produce any crops. So we need the UAE and international support to help us or more people will turn to violence and the sea.”