Friday cricket is ritual for thousands of people across the UAE. For the vast majority, that means vying for room in a dusty street or a car park, rather than on neatly manicured grass fields with a rolled flat wicket to bat on.

Stumps are rudimentary. Bats are whatever the players can lay their hands on. And the balls are not the conventional cork and leather ones of cricket’s mainstream, but tennis balls wrapped in electrical tape to make them fly faster.

The players might be friends, but the competition is fierce. And talent is everywhere. Some have even shown it is possible to go from a street on the remote east coast of the UAE to the heights of the international game.

7.30am. A Friday during Ramadan, in a car park in the middle of Al Quoz industrial estate, Dubai.

While his teammates crouch between two Isuzu utility vehicles to shade themselves from the early morning sun, a batsman removes his sandals and stands in front a set of thin metal stumps.

It is an internal match between the staff of a construction firm, in the nearest car park to their company accommodation in Al Quoz. A friendly, as it were. Although it doesn’t seem so friendly just at the moment.

With the Burj Khalifa cutting into the blue sky behind him, a bowler runs in, and hurls the ball down, full tilt. The batsman swings and, it appears, misses.

And there is about to be a row.

“Out!”

“Not out, yaar!”

Words which, judged by the tone in which they are delivered, might well include expletives, are shouted between the opposing players in Tamil, Malayalam and Hindi.

Players are extremely resourceful when it comes to equipment

Then Prathab Selvaraj, the company’s HR manager, steps in and makes a ruling.

Out. Innings over. Only 38 required to win from 12 overs. Too easy.

“No problem,” PV Charan, a fielder whose day job is as a draftsman, says with a triumphalist smirk. “And we won the first game, too.”

The players are halfway through the second game of the day, and it is not yet 8am.

This is how Friday mornings look for thousands of workers across the UAE.

There are at least a hundred in this car park alone. Five matches are taking place, side by side, with the full quota of 11 players in most teams.

A classic street cricket sight - the big leg-side heave

A handful are wearing full cricket whites. Some wear football shirts, with AC Milan and Benfica noticeably represented. Most just wear casual clothes.

This is a sizeable space, around 250 metres by 200 metres. But with this numbers of players, it still feels cramped. Matches overlap, with some fielders in one match being at the centre of the action in the neighbouring game.

This is prime real estate for street cricket. As such, the earliest risers get first dibs on the best spaces to play.

The players involved on the match on the far edge of this plot (furthest from their accommodation, but with one side of the pitch free from other matches) have Shahab Faisal, a 29-year-old Indian from New Delhi, to thank.

“I woke up at 3.30am for sehri [suhoor], the food we have before we have to fast,” he says.

“After that, I went for namaz [prayers] at the mosque behind our street, then I came here to occupy this place. We didn’t want anybody else to occupy this because it is the place that is most in demand.

“It is most undisturbed. We can play here alone. The place alongside that one, and alongside that one, there are two or three teams playing on that street already. But where we play, there are no other people on the offside.”

Shahab volunteered for the job on the players’ WhatsApp group. He was happy to take one for his team.

“Anyone can go, we decide on the group, but during fasting I prefer to wake up early and go,” he says.

“It is better for me to go and get the place, then after half an hour, or 45 minutes, at 5.30am, everyone else comes.”

The match mostly involves players who live in and around Al Quoz, the sprawling industrial area in Dubai, but some have come from further afield. Kishore Mhatre, for example, left his home in Sharjah at 5.50am to come and play. He brought his six-year-old son Kanav along, too.

Players find some shade to escape the searing heat

It seems like a remarkable undertaking just for a knockabout game of cricket, but the players would not miss it. It is a ritual, not just about playing sport, but about meeting up with friends.

“Sometimes there is 10, nine, eight players in one team, but we try to get 20 to 22 people so we can play properly,” says Pravin Shetty, 31, from Mumbai.

“We don’t have time in the office to talk, or have group discussions. This is our best means of communication, and for getting together. Most of the players have families. In the evening time, they prefer to spend time with their family.”

The players are all expatriates who have come to Dubai from the subcontinent for work. Friday morning cricket is a little slice of home.

“In India, the craze is for cricket,” Shetty says. “They start early in the morning, and carry on until three or four o’clock.

“Most of the Europeans [in their company], they don’t stay around this area. And these people are mostly managers. We are on the lower level, we work in admin, so we play. The managers won’t come to play with us. They have separate interests, like golf.”

At the moment, matches are mostly finished by 9am because of the summer heat. In the cooler winter months, though, play can last all day.

During summer months play is usually restricted to mornings and evenings

“There is no limit in India to playing cricket,” Faisal says. “Here, it is only the heat. In winter, we play maximum five matches. The team who win the majority are the winner.

“During the game we are not friends; we are competitors and rivals. We need aggression to make the games fun. But afterwards, we are friends.”

So, they want to know, why the sudden interest in their game?

“Are you the UAE selectors?” asks one of the fielders on the edge of the middle match in the car park. His broad grin made it clear he already knew the answer.

Of course not. That would be ridiculous. Why would they be looking here? Nobody could make it from playing with a taped tennis ball in a car park to the international game.

Could they?

How one of the world's leading bowlers, still turns out to play tape-ball cricket with his friends

Mohammed Naveed played in cricket’s World Cup in 2015. He dismissed the sport’s then leading batsman, Hashim Amla, among others, while he was there.

He hit Ravindra Jadeja for six off his first ball. And Dale Steyn, too.

He is currently ranked the 11th best bowler in the world in Twenty20 international cricket, and has designs on a place in the top 10 as soon as possible.

He earns two salaries via cricket, and says he is very comfortably off as a result.

And despite all that, he thinks nothing of driving two hours through the Hajar Mountains from Sharjah to play tape-ball cricket for free with his friends in Khor Fakkan on the east coast.

Tonight’s game, in an organised tournament involving 20 teams, begins at 11.30pm. He drove the 150 kilometres from his home near Rolla Mall on the evening of the game.

Mohammed Naveed - one of the world's best - is perfectly at home with a

tape ball in hand

After the game, at around 1am, the team have dinner together, before Naveed bunks down in one of their rooms, then travels home in the morning.

“I love it when I come to play here,” Naveed says. “I do this because my friends love me and respect me.”

He has not forgotten what got him where he is in cricket. Just before the turn of the decade, he arrived from his home Jhelum, a city around 100kms south-east of the Pakistan capital Islamabad, on a tourist visa to visit friends in Fujairah. He is not even close to going back.

Now he is an international cricketer with his adopted country. The route he took to get there was a circuitous, but beautiful one.

Naveed will travel for hours to play with his friends

After impressing everyone while playing tape-ball cricket in the streets on the east coast, his friends suggested he go to Sharjah to try to catch the eye of the UAE selectors.

He took a public bus to nets at Sharjah Cricket Stadium, a journey that took three hours there, three hours back.

He bowled 10 deliveries in front of Aaqib Javed, the former Pakistan player who headed cricket in the UAE between 2012 and 2016. The national team coach was hooked, immediately calling him into his team.

Naveed's cricket skills earned him employment. He is paid a salary by United Bank Limited, or UBL, nominally for a job in their accounts department, but mainly to represent their staff cricket team.

He does this (naturally, as the leading pace bowler in the country, with distinction) on the neatly kept grass fields of Sharjah Cricket Stadium and the Zayed Cricket Stadium in Abu Dhabi. His wages are further topped up by a retainer to play for the national team.

Naveed is proud of the fact he earns well from cricket. He is content to bear the costs of the regular speeding tickets he says he has incurred in getting to matches, although he was grateful for the discount offered on paying the fines during Ramadan.

Despite his salaried commitments, he still chooses to make a round trip of over four hours to play for free with his friends in Khor Fakkan as often as time permits.

“People enjoy their work when they get a lot of respect,” he says. “Money is not as important to me. Respect is. Respect and love. They are both important in life. That's why I come here.

“When I started off, my goal was to play for the national team, and play good cricket. People would ask me why I was working so hard and what my aim was.

“When I would tell them I wanted to play for the UAE one day, they would assume I was joking. I worked hard from the very beginning, right. And I was always determined to achieve my goal.”

One goal was ticked off when he debuted in international cricket. The next is in sight.

“If I reach the top 10, my dream would be achieved – that I would be among the top 10 bowlers in the world,” he says.

Being a UAE national team cricketer does not confer quite the stature players receive in countries such as India, Pakistan, Australia or England.

But Naveed does have some celebrity. As he idles away time before his match for Babar Cricket Club in Khor Fakkan, a man takes a break from selling chai at a pitch-side stall to take a selfie with him. He is not the only one.

His mates enjoy Naveed’s stardom even more than he does.

“Here, 90 per cent of the people have only come to watch Naveed,” says Sami Ullah, a long-term friend of his from back home in Pakistan, who is now in charge of marketing for a money exchange company in Fujairah.

He is referring to the hundred or more spectators who line the boundary, sat on anything from rudimentary wooden benches and bleachers, to - randomly - a felt armchair.

Even though it is approaching midnight, there is a good crowd assembled for what might be one of the hottest tickets in Khor Fakkan tonight.

Fans will attend matches simply to see world No 11 bowler, Naveed

“They want to see the international cricketer,” Sami says. “His pace is very good. His batting style is very good. People are inspired by Naveed’s cricket.

“They want to come here and take selfies with him. He is very famous. He has played ICC World Cup in 2015, so people only come here for Naveed. Everybody likes his style.”

Naveed has the twin attributes of the archetypal tape-ball champion: he bowls fast and hits big sixes. When he played at the World Cup in 2015, his main goal for the competition was not, as the leader of the UAE bowling attack, to take wickets and send down 10 thrifty overs for the good of the team.

All he cared about was hitting Steyn, the game’s fastest bowler at the time, for six. He managed it, too, hitting the fearsome South African quick 20 rows back in a game in Wellington. Earlier in that game, in his main suit as a bowler, he had taken the wicket of Amla, but he was less fussed about that than his batting exploits.

Not surprisingly, his cheer squad back on the UAE’s east coast were thrilled.

“During the World Cup, we were in one room and there were 40 to 50 people there, sitting and watching,” Sami says.

“When Naveed came on to bowl, we were loudly shouting, ‘Naveed! Naveed!’ like that. When we saw him on TV we were very happy. After the match we called him from here, telling him his pace was good and we were happy for him.

“We thank UAE for giving a chance to Mr Naveed to play international cricket. Inshallah, he will be in the top 10 bowlers in the world.”

More than anywhere else in the Middle East, Sharjah is synonymous with cricket.

First played at the Royal Air Force base in the 1950s, cricket took hold when Abdul Rahman Bukhatir, an Emirati who became a successful businessman, fell in love with the sport while studying in Pakistan.

He funded the construction of a cricket ground in his home emirate, and the game flourished from the start of the 1980s.

As well as a stadium of great renown, Sharjah also gave international cricket one of its all-time favourite players. Or at least played a small, but key role in his development.

Waqar Younis lived there for five years as a child, after his father was posted to work in Sharjah port, then later in Dubai and Abu Dhabi, too.

One of the earliest memories he has of the game he went on to grace as the captain of Pakistan and one of its premier fast bowlers is from a trip to watch a match in Sharjah.

Waqar, right, has fond memories of cricket in the UAE

“We didn’t live too far from the stadium,” Waqar says. “I have a great memory of seeing Imran Khan playing there. He was a youngster, very young, maybe a teenager.

“I remember that because later on I played under him. He was almost retiring, but I got to play under him for a couple of seasons. I always cherished that because he was someone I had seen play in my childhood and then I got to play with him. It was very special.”

Now Sharjah Cricket Stadium has staged more one-day internationals than any other ground in world cricket. On any given match day the action outside the stadium is usually every bit as fevered as inside.

Innumerable tape-ball matches are played on whatever ground is spare in the surrounding area in Sharjah Industrial Area 5. This includes wasteland next to the down ramp of Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nayhan Road, meaning fielders have to be wary of juggernauts doing 80kph just past the boundary.

And, even if many of the bays have been filled by cars of the spectators for the big match, matches still go on in the car park adjacent to the neighbouring football stadium.

Waqar says he played “very little” tape-ball cricket in his youth, either in Sharjah or Pakistan. When he did, it was “just for fun, nothing to be learnt from it”.

He added: “Tape-ball cricket helps the batsmen more than the bowlers. It comes a little bit quicker off the surface because of the tape. The bats are lighter, your hand-eye coordination has to be better.”

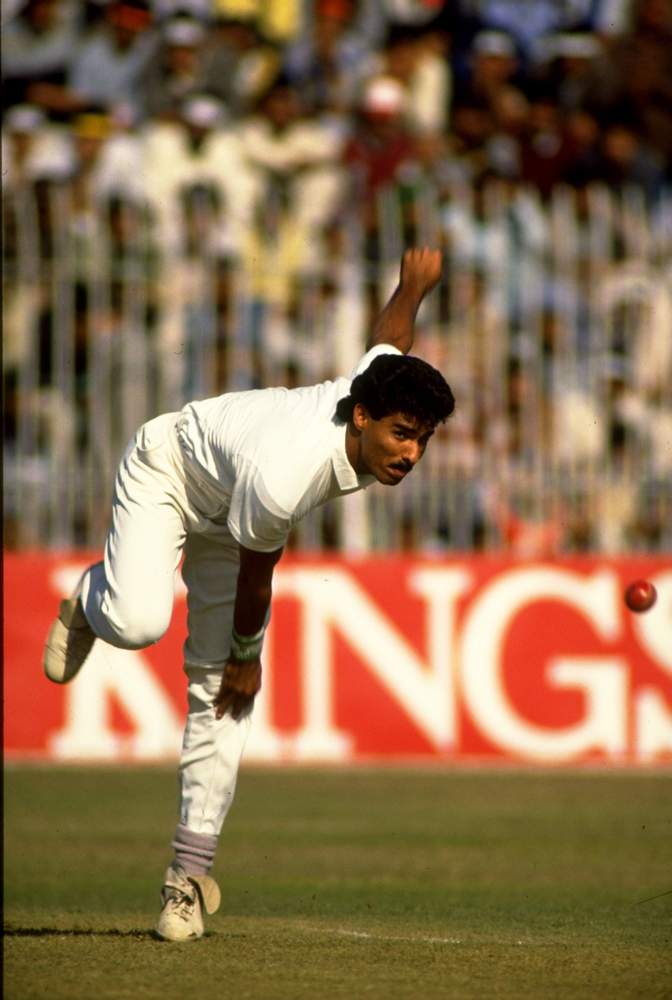

Waqar Younis in his playing days

Some coaches swear by the merits of tape-ball cricket. Aaqib Javed, who won the World Cup as a bowler for Pakistan in 1992, first gave Mohammed Naveed, the Fujairah tape-ball cricketer, his chance in international cricket, when he was coach of UAE.

He thinks bowlers who learnt the game using a tennis ball wrapped in tape are automatically conditioned to bowling fast.

“It takes a lot more effort than a cricket ball, especially bowling yorkers,” Aaqib, a long-time teammate of Waqar’s, said. “When you are playing tape-ball cricket, you have to be smart.”

Waqar is cool on the relevance of the recreational version of the game on him, even though his bowling method might be said to have betrayed many signs of a tape-ball champion.

He puts his distinctive “slingy” bowling action down to the modifications he made to deal with the pain of a back injury suffered early in his career, rather than tape ball.

“I played, it is not that I didn’t, but to say that it helped me increase my speed, I don’t think so,” Waqar says.

“I was very natural when it comes to speed. Maybe some actions can be improved on because of it, but it didn’t work for me. Of course, when I was playing tape-ball cricket, I never thought I would go on and play for the country.

“I broke my back very early in my career. I didn’t remodel my action, but it gave way to certain parts of my body that were aching at the time, and my body adjusted to it, and my action got slingier.”

The Tape Ball

Street cricket in the UAE is mainly the preserve of subcontinental expatriates, but each game carries with it intricate regional differences.

That is the view of Prasanna Ranjith, a Sri Lankan who has been organising street cricket tournaments in Dubai for over a decade now.

His matches are played with a tennis ball (Dunlop or Wilson are his preferred manufacturers) wrapped with electrical tape. Ten rolls of tape cost around Dh10.

That is not the form of the game he and his compatriots are most used to, though.

“Once I invited a Pakistani team, Akhtar CC, named after the fast bowler Shoaib Akhtar, to play,” he says. “They won the tournament, we were the runners-up. They were very, very tough. Tape-ball cricket comes from Pakistan.”

Before making it to the international game, Lasith Malinga, the Sri Lankan fast bowler, modified his idiosyncratic “slingy” action to suit playing with a tennis ball on the beach.

Ranjith says Malinga and his compatriots would traditionally have used a different method to make the ball aerodynamic, rather than covering it in tape.

“In my country, we never played with a tape-ball, we played with a normal tennis ball,” he says. “Sometimes we will burn the ball, then other times we will cut the ball with a razor. After that the ball will fly more quickly.”

King for a day

Tape-ball cricketers live to be considered the champion of their street, or the car park. They want to be king for a day, even if the intense summer heat of the UAE, for example, means games can be over before breakfast.

As the world’s No 11-ranked Twenty20 bowler, Naveed has a strong claim to being the leading cricketer in the country. He might not even be the best street cricketer in his own house, though.

Mohammed Shahzad, best known as Mana, is Naveed’s housemate. A UAE international up until recently, he is a street cricket star.

Those who know claim that spectators used to travel across Gujranwala, his home city in Pakistan, just to watch Mana playing tape-ball cricket, before he made the move to UAE.

The shy 37 year old baulks at the idea. “Did he tell you that?” Mana asks, nodding towards his smiling housemate Naveed. “He is a liar.”

Mana Shahzad, left, watches on with Mohammed Naveed

The evidence in Khor Fakkan suggests Mana’s modesty is misplaced. It is past 1.30am now, on a work night, and people still line the boundary to watch him play in his second match of the night.

“I played a lot of cricket, and good cricket in Pakistan, which is why people liked me,” he says. “I don't feel under any pressure in front of the crowds.”

Street cricket is rent with machismo. Bowlers propel the ball as fast as they can, targeting head or stumps. Batsmen, as a rule, try to bludgeon the ball as far as they can, usually straight back past the bowler, or heave to the leg-side.

Mana’s method differs from the wild windmilling of others. He deflects the ball in whichever direction he chooses. When he does deign to hit a six, it makes a different noise off his bat than the rough slap others make.

Like Naveed, it was cricket that kept him in the UAE, after he initially arrived on a tourist visa.

“I came here on a visit, only for playing cricket,” says Mana, who represented his state at tape-ball cricket age 10, and only played hard-ball cricket for the first time when he was 15.

“I performed well. My first company gave me a visa and I got to stay. There was no way to support my family [in Pakistan], so I stayed here to help them.”

Late night at Khor Fakkan and the play shows no sign of stopping

He is doing the same thing now, too. Mana was among the first batch of eight players to land a deal to play professionally when the Emirates Cricket Board, the sport’s governing body, offered central contracts for the first time last year.

He has since been cut loose, though, with the selectors citing his age as the issue. Losing his job has meant starting over.

His wife and young daughter remain in Pakistan, while he is trying to set up in business in Sharjah, having invested in a 50-tonne crane with his earnings from cricket.

“I will stay,” he says. “I have started my own business, Alhamdulillah. After that I will get visas, go back and bring my family here.”

To make a go of business, he plans to retire from organised, hard-ball cricket. But he will find it impossible to let the street version go. “This is for fun,” he says. “I will continue … only for fun.”

Credits

Words: Paul Radley

Images: Pawan Singh, Chris Whiteoak

Video: Emmanuel Samoglou, Paul Radley

Editing: Steve Luckings, Chitrabhanu Kadalayil